The China Deep Dive

China has long been a subject of scrutiny for investors, economists, and financial media. It's a place where investors are divided into two camps: those who believe it's a fragile economic structure, and those who envision it as the superpower poised to surpass the United States and become the world's dominant economy. In this article, we will conduct an in-depth analysis of various aspects of China. We will begin by examining current developments at ports, import/export trends, fiscal factors, and conclude by assessing the prevailing state of monetary policy in China.

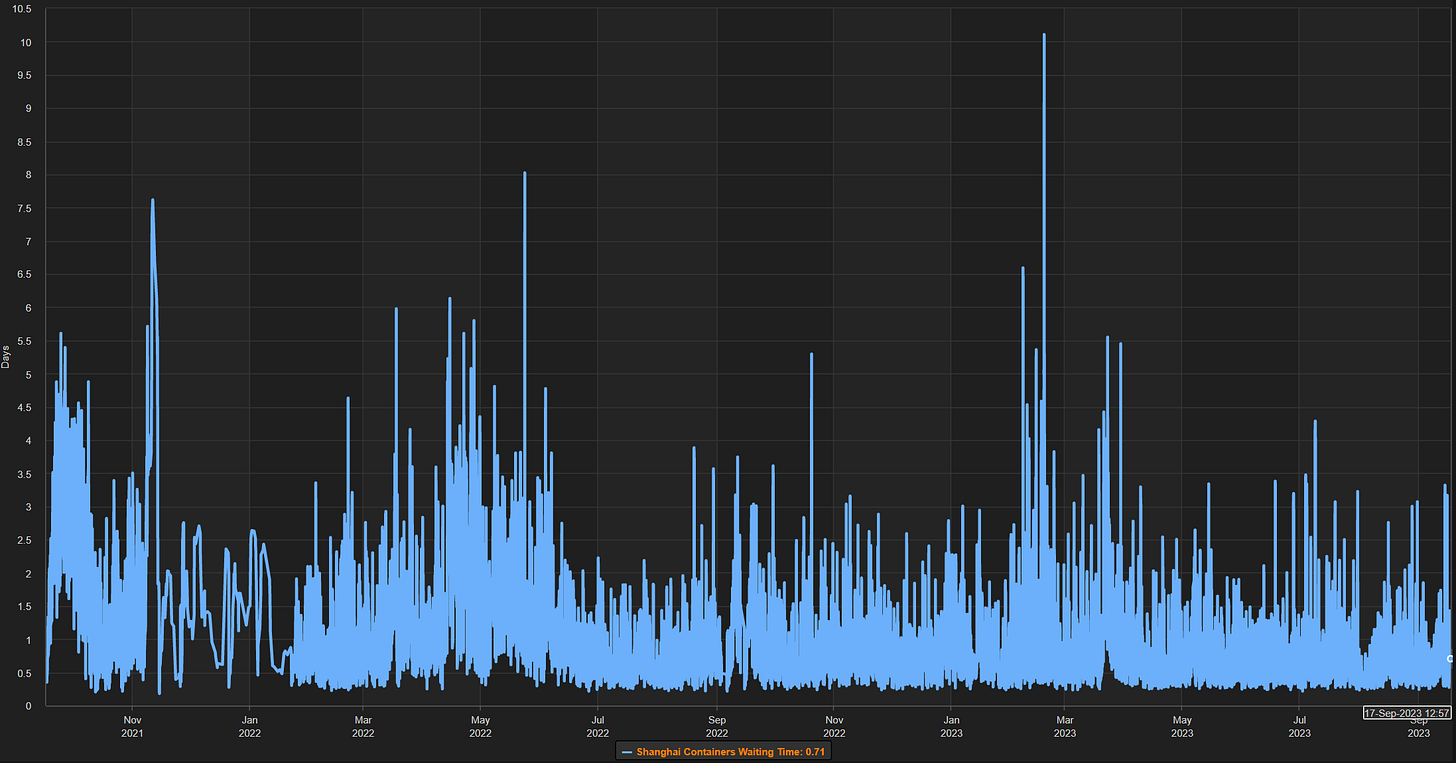

Many people expected that China's reopening would resemble a grand and magnificent event, sparking a surge in demand and global trade activity on Chinese shores. However, as of now, this scenario has yet to materialize. There is no evidence of significant congestion or prolonged waiting times at Chinese ports. Figures 1 and 2 below illustrate different aspects of Chinese ports at present. As depicted, current wait times are relatively low compared to the past few years (barring the impact of COVID-19). Figure 2 provides a more comprehensive view of extended wait times at Shanghai, which again remain exceptionally low when compared to the previous couple of years. Generally, heightened levels of congestion tend to coincide with increased export and import activity. Setting aside the influence of COVID-19, the current sluggishness in port congestion suggests a deceleration in both Chinese exports and imports.

(Figure 1)

(Figure 2)

This leads us to examine the trade statistics. In the most recent import and export data, when considering the year-over-year percentage change, imports have decreased by -7.3%, and exports have declined by -8.8%. This decline is somewhat perplexing, especially when we take into account the current value of the yuan. With the yuan's depreciation, one might expect exports to rise, as China becomes more competitive in global markets due to its ability to export deflation. However, as a result of this phenomenon, industrial profits are inevitably taking a hit, as they indeed have. This should theoretically be a period during which we witness robust exports for China. However, that has not been the case. Figure 3 illustrates the year-over-year changes in imports and exports for China.

(Figure 3)

On the topic of exports, it's worth noting that China's share of US imports has been on the decline, with Mexico surpassing it. What's intriguing in Figure 4 is that when we examine the purple line, representing the ratio of the prices of imported goods from China to those from Mexico, one might expect that as Mexican goods become more expensive, we would observe a decrease in Mexico's share of imports and an increase in China's share. However, this is not the case. What we are witnessing is a shift in the US away from China and toward Mexico in terms of imports. Simultaneously, in terms of the developments in the purple line, we see that the terms of trade are deteriorating for China but improving for Mexico.

With that being said, let's delve into some of the fiscal factors. Government expenditures have been on the rise, which is not surprising given China's aging population. As the population ages, it is expected that government spending will increase. Figure 5 provides a breakdown of China's current government expenditures. It's evident that social security and employment have been significant contributors to these expenditures, along with education. Healthcare, although relatively small in comparison, is likely to see an increase in allocation as the population continues to age.

What does this all mean? Increased government expenditure can compress and even make negative the government expenditure multiplier. This, in turn, leads to further decreases in private sector GDP. Additionally, it often results in more transitory impacts from any kind of stimulus, which tend to dissipate quickly.

(Figure 5)

Another intriguing aspect of China is its approach to setting growth forecasts. They establish growth projections and then effectively mandate that provinces meet these targets. However, the majority of provinces can only achieve these forecasts through incurring debt or running deficits. When we examine provinces throughout China, it becomes evident that each one, with the exception of Shanghai, is operating with a deficit. This implies that a significant portion of the debt incurred by these provinces is either not put to productive use or is directed towards funding real estate and other endeavors rather than being channeled into investments in tangible economic assets that can enhance productivity and capital per worker. This is shown in Figure 6 below.

(Figure 6)

Finally, let's examine the national government fund analysis for China. The national government fund continues to display a deficit, which can be attributed to several factors. However, focusing on the past few years since the onset of COVID-19, we can see that the Chinese economy has faced significant challenges. One of the primary sources of tax revenue for China is the value-added tax (VAT), which has come under considerable pressure and has experienced a rapid decline (as depicted in Figure 7). To counter this, China implemented tax rebates, contributing to a significant portion of the decrease in VAT revenue. The objective was to stimulate domestic spending and rejuvenate China's sluggish economic growth.

Another substantial decline in revenue stemmed from the collapse of the Chinese property market, leading to reduced taxes on land values. As illustrated in Figure 8, these taxes constituted a substantial portion of the government's income. With the persistent pressure on the real estate market, the Government Fund Analysis now shows China running a deficit. There has been a substantial increase in expenditures, but the income generated is insufficient to offset these expenditures. Consequently, China finds itself in a deficit situation. Much of this can be attributed to the diminishing marginal returns on debt that China appears to be experiencing.

(Figure 7)

(Figure 8)

As discussed earlier, the real estate sector has played a significant role in the Chinese economy. Unfortunately, the current situation in this sector does not paint an optimistic picture. Mortgage loans have experienced a substantial decline when considering the four-quarter percentage change. Historically, an essential driver of credit demand in China has been the growing demand for mortgages. However, with the decline in mortgage loans, there is potential for added strain on the Chinese economy, as depicted in Figure 9.

(Figure 9)

China has attempted to address this issue through liquidity injections, but these efforts have yielded limited results. I have previously discussed the emerging liquidity trap in China, and I will briefly touch upon it again. A liquidity trap occurs when governments, typically through their central banks, attempt to stimulate consumption and spending by lowering interest rates. They aim to incentivize borrowing by reducing interest rates. However, what we are observing is that despite recent increases in overall liquidity, the demand for loans remains weak. This essentially defines a liquidity trap.

In Figure 10 below, you can see the current status of net liquidity injections, which have indeed increased. However, even with this heightened injection of liquidity, the outcomes have been far from robust.

(Figure 10)

There has been a noticeable uptick in social financing in China, primarily driven by an increase in CNY loans, which historically have been the main factor influencing fluctuations in social financing. However, I've maintained the viewpoint that a significant portion of this increased demand originates from the public sector, rather than the private sector. This becomes evident when examining areas like mortgage demand and other types of loan requests from the private sector, which have remained relatively sluggish. While some might argue that the current easing measures have yielded positive results, I would contend that the bulk of this effect is driven by public sector demand aimed at stimulating the economy. This can be seen below in Figure 11.

(Figure 11)

Taking all of these factors into consideration, it's clear that China is currently experiencing a slowdown. Port activity has decelerated, as evidenced by reduced congestion, indicating a corresponding slowdown in import/export activity. The fiscal situation is problematic, with deficits on the rise and a substantial decline in tax revenue. This will likely place additional strain on provinces as they grapple with declining tax revenues.

Furthermore, the growing liquidity trap and the weak real estate sector have hindered efforts to stimulate consumption through low interest rates. All of these indicators point to challenges for China as we approach the end of the year and the beginning of 2024. It's a situation that warrants close attention. For the time being, my outlook for the Chinese economy remains pessimistic.