Tariffs

Introduction

Anyone who has seen the news lately has likely been exposed to the ongoing discussion about tariffs. This comes on the heels of anticipated higher tariffs from the USA being imposed on its trading partners. Within this discussion, there has been considerable misunderstanding about the impact of tariffs on the economy, particularly regarding whether they increase consumer prices. These topics will be discussed in this Substack.

Economic Theory

A tariff is essentially a tax imposed on imported goods. When a country introduces tariffs, it makes foreign products more expensive compared to domestic products. The goal of tariffs is often to protect local industries from foreign competition, promote domestic production, and generate revenue for the government.

Imagine you’re a consumer in the U.S. and you regularly buy a particular brand of electronics made overseas. If the U.S. government raises the tariff on these electronics, the cost of that foreign product will likely rise. As a result, the price difference between that imported product and a similar, locally-made product may decrease, making domestic goods more attractive.

The economic theory of tariffs centers around the idea that they disrupt free trade, which can lead to both positive and negative consequences. Let’s break this down further.

One of the primary reasons governments impose tariffs is to protect local businesses. By making foreign goods more expensive, tariffs encourage consumers to buy domestically produced items, helping local industries grow. For example, a U.S. car manufacturer might benefit from a tariff on imported cars because it makes foreign cars less competitive in terms of price. This protection can lead to job creation in domestic industries.

Tariffs are also a way for governments to generate revenue. When foreign goods enter the country, they are taxed, which increases the funds available to the government. This revenue can then be used for public services or infrastructure projects. In some cases, this can be especially beneficial for governments that rely on tariffs as a significant source of income.

On the flip side, tariffs often have a direct impact on consumers. Since foreign goods become more expensive, domestic businesses that rely on importing materials or finished products can face higher production costs. In many cases, these increased costs are passed on to the consumer in the form of higher prices.

For example, if a tariff is imposed on steel imports, companies that manufacture cars, appliances, or buildings using steel will see a rise in their production costs. To maintain their profit margins, these companies may raise the prices of their products, which could ultimately lead to inflationary pressures in the economy.

Tariffs can lead to trade wars, as countries retaliate by imposing their own tariffs. For instance, if one country raises tariffs on another country’s goods, the affected country may retaliate by raising tariffs on the first country’s exports. This can disrupt global supply chains and make goods more expensive for everyone involved.

This cycle can harm consumers and businesses alike, especially if the countries involved are major trading partners. For example, if the U.S. imposes tariffs on China, China may retaliate by imposing tariffs on U.S. agricultural products, hurting American farmers.

Economists often argue that tariffs can lead to inefficiencies in resource allocation. By protecting domestic industries from competition, tariffs prevent markets from fully realizing their comparative advantage—the principle that countries should specialize in producing the goods and services that they can produce most efficiently.

For instance, if the U.S. imposes tariffs on cheaper foreign steel to protect its domestic steel industry, the U.S. may end up producing steel at a higher cost than other countries. As a result, resources that could be used more effectively elsewhere in the economy are tied up in less efficient industries.

Tariffs in Reality

In the short run, the relationship between tariffs and the NEER is more easily explained by the regression model, as evidenced by the higher R². However, in the long run, this relationship becomes less explanatory as other factors begin to influence the NEER in addition to changes in tariff rates.

This dilution of the tariff's impact leads to a lower R² over time. Despite the lower R² in the long run, the p-value remains statistically significant, indicating that tariff rates still have an impact on the NEER, even over a longer time horizon.

This suggests that while the relationship becomes more complex, the model's coefficient remains statistically significant, and the effects of tariffs on the NEER are both real and meaningful in the long run.

In the short run, the smaller p-value can be attributed to greater volatility in the effects, which increases the degree of noise and variation in the model. This higher variability reduces the p-value relative to the long run. Nevertheless, the regression results confirm that this relationship remains important.

The p-value in the long run is 0.00000603, which indicates a very high level of statistical significance. This small p-value suggests that there is a very low probability that the observed relationship between tariff rates and NEER occurred by random chance, allowing us to deduce that the tariff rate has a meaningful effect on the exchange rate.

The t-statistic of 4.73964 further supports the statistical significance of the relationship, confirming that it is not due to random variation.

The coefficient is 0.51, meaning that for each 1% increase in the tariff rate, the effective exchange rate increases by 0.51%, holding other factors constant. Therefore, we can reject the null hypothesis.

Null hypothesis (H₀): The coefficient of the tariff rate (X) is zero, implying that tariff rates have no effect on the NEER and there is no relationship between the tariff rate and the NEER.

Alternative hypothesis (H₁): The coefficient of the tariff rate is 0.51, meaning that tariff rates do have an effect on the effective exchange rate.

In the short run, the p-value is 0.000256, which is again smaller than the significance threshold of 0.05. This indicates that the null hypothesis can be rejected, meaning there is statistical evidence that tariff rates affect the NEER even in the short run.

The t-statistic of 5.113183 is well above the threshold of 2 for the 95% confidence level, suggesting that the coefficient is significantly different from zero. We can conclude that the tariff rate has a substantial effect on the NEER in the short run, and the coefficient is not due to random chance.

The coefficient of 0.41 means that for each 1% increase in the tariff rate (X), the effective exchange rate (Y) increases by 0.41%. So we can see if tariffs do materialize USD should be a large beneficiary.

(Regression does cluster around 0 as Tariff rate might not change, more stripping out of outliers must be completed. This is a rough draft of highlighting effects).

Conventional economic wisdom would suggest that during periods of a high output gap, increased tariffs would have a larger effect.

During periods of a high output gap, there is already a demand-supply imbalance, which puts upward pressure on the price level. When tariffs further restrict supply, it would put additional upward pressure on the price level.

However, the regression finds the opposite to be true.

The low coefficient for the interaction term (Output Gap * Tariff Rate) might initially seem counterintuitive, especially if you expect that a higher output gap combined with a high tariff rate would amplify tariff revenue significantly.

If demand for imported goods is elastic, then higher tariffs combined with a larger output gap might actually reduce the quantity of imports more than expected, which could offset tariff revenue gains.

A higher output gap often indicates an overheated economy, where domestic production and consumption are strong. High tariffs in this environment could incentivize businesses to find alternative sources, reduce import demand, or change supply chains, leading to a smaller-than-expected increase in tariff revenue.

If both tariffs and the output gap are high, the combined effect might suppress trade volumes significantly. For example, businesses might respond by reducing import orders to manage costs, leading to a net decrease in tariff revenue, even if tariff rates are high. This is especially likely if the tariffs are set at a rate where they become a significant barrier to trade rather than just a revenue-generating tool.

Sometimes interaction terms have counterintuitive results due to multicollinearity with other variables. If the output gap and tariff rate individually capture much of the effect on PCE, you will see a reduction in the interaction term as it adds less unique information.

Now to the findings: the p-values for the Output Gap (0.000597), Tariff Rate (0.002), and Interaction (0.019967) indicate the statistical significance of each variable. With p-values below 0.05 for all three variables, we can conclude that the Output Gap, Tariff Rate, and their interaction significantly affect PCE.

The coefficients for the variables show that for each unit increase in the Output Gap, PCE is expected to increase by about 1.237 units, assuming other variables remain constant. For each unit increase in the Tariff Rate, PCE is expected to increase by about 1490.165 units, holding other variables constant. The interaction term’s negative coefficient of -215.093 suggests that when both the Output Gap and Tariff Rate increase together, the impact on PCE is lessened by about 215.093 units.

Tariff Rate is a highly significant predictor with a strong positive effect on PCE, and the Output Gap also has a positive and significant effect on PCE. The Interaction Term suggests that when both the Output Gap and Tariff Rate are high, the effect on PCE is moderated (reduced). Since all predictors except the intercept are statistically significant, we can conclude that the model is robust.

The R-squared value of 0.3561 (or 35.61%) in your multiple regression analysis indicates the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (PCE) explained by the independent variables (Output Gap, Tariff Rate, and the Interaction Term). This means 35.61% of the variation in PCE is explained by the combined effects of the Output Gap, Tariff Rate, and their interaction, leaving about 64.39% of the variance in PCE unexplained by the model. This suggests that other factors outside of these variables also influence PCE.

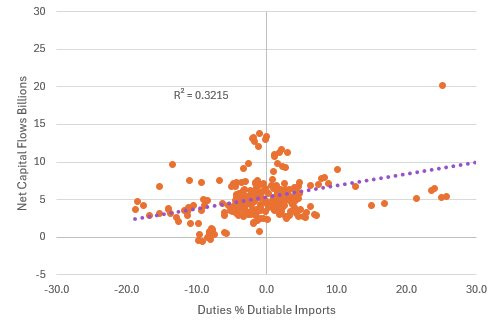

Examining the impact on capital flows. The y-intercept is 528.2, which represents the value of Y when X = 0. The slope of the line is 2.778, meaning that for each one-unit increase in X, Y increases by 2.778 units.

The T-statistic of 8.05 indicates strong evidence to reject the null hypothesis. The p-value is essentially zero (3.25E-14), further supporting the rejection of the null hypothesis.

Interestingly, despite an increase in duties, we observe that capital flows rise. This is paradoxical because, in theory, higher duties should restrict trade.

One possible explanation is that nations with large current accounts avoid current account deficits. If a country increases duties, trade partners may face reduced export revenue. However, those nations will continue to export to other countries and need to park the resulting cash somewhere. Since nations running current account surpluses must, by identity, run capital account deficits, they will continue to park cash in other nations.

Firms might also engage in Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) to avoid tariffs, as Japan did under Reagan with its automotive industry.

Additionally, financial flows can increase due to factors other than trade, such as higher interest rates, better investment climates, stronger institutional quality, better regulation, and protection of property rights.

Moreover, as tariffs tend to weaken the affected country's currency, making it less attractive for investment, this can drive capital flows into more stable nations with stronger currencies.

While the R² isn’t very high due to other variables affecting capital flows, the regression still shows that tariffs can lead to an increase in capital flows to a statistically significant degree.

While it is often assumed that tariffs lead to significant price increases across the economy, the actual impact on the overall price level tends to be minimal, if any. In fact, various factors, such as exchange rate movements, often offset the expected increase in tariff rates. Let’s take a closer look at how these dynamics play out.

When tariffs are increased, one of the immediate reactions in the global economy is the potential movement of exchange rates. For example, if the U.S. imposes higher tariffs, it could lead to a stronger U.S. dollar as traders anticipate reduced trade flows. A stronger dollar can mitigate the price increase that would otherwise result from the tariff. In many cases, this appreciation of the dollar acts as a counterbalance, helping to keep inflation in check despite the tariff hikes.

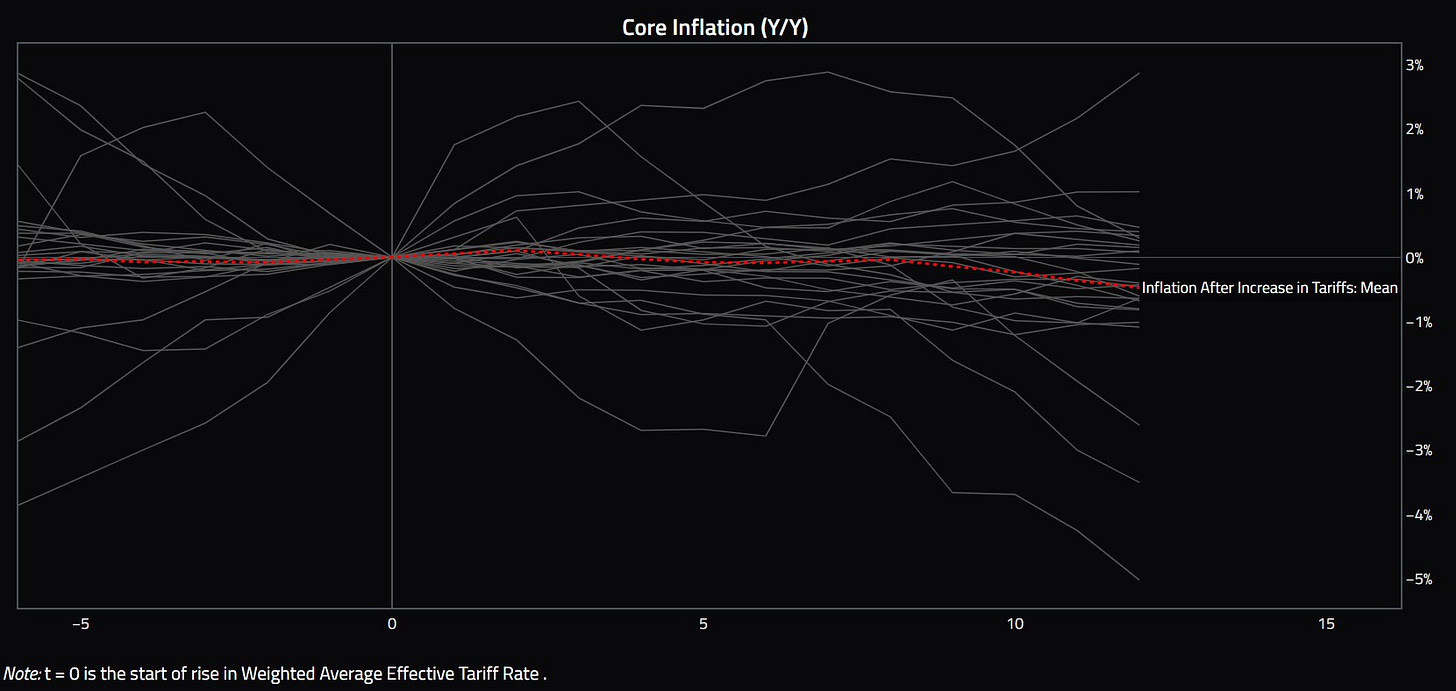

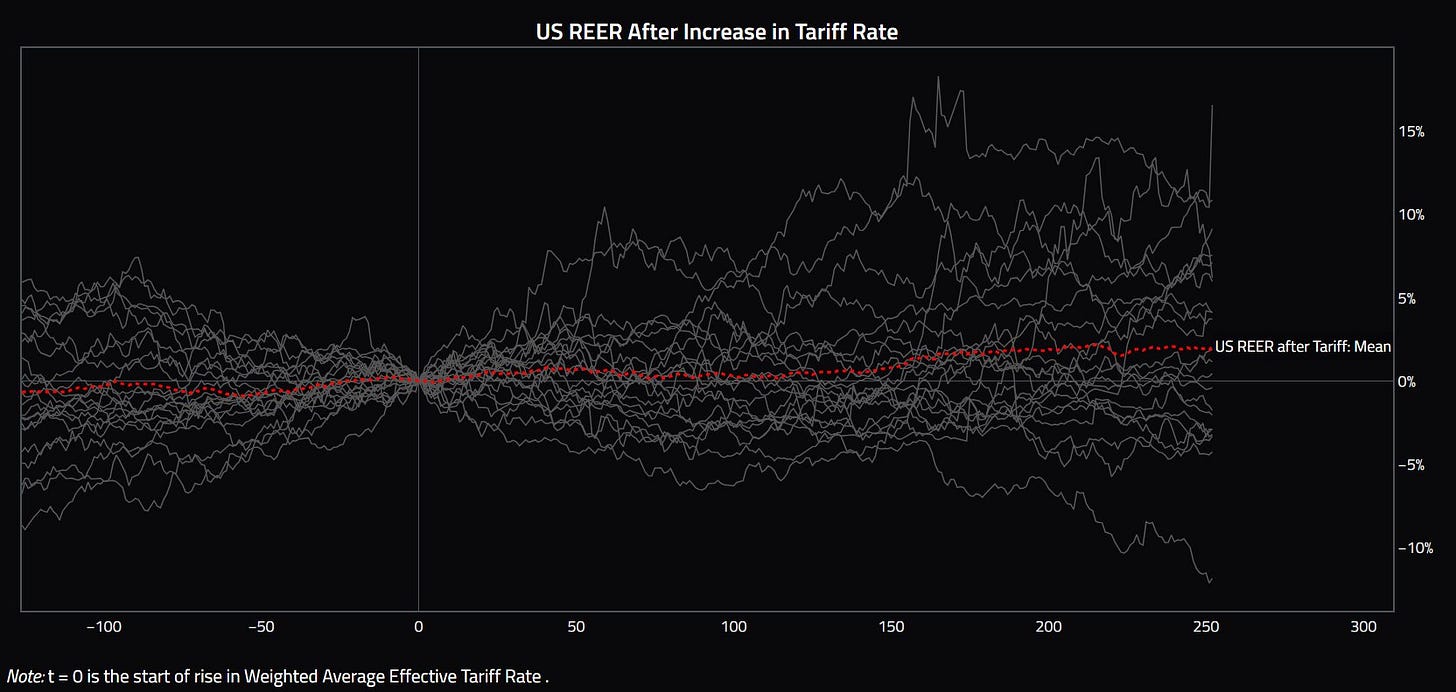

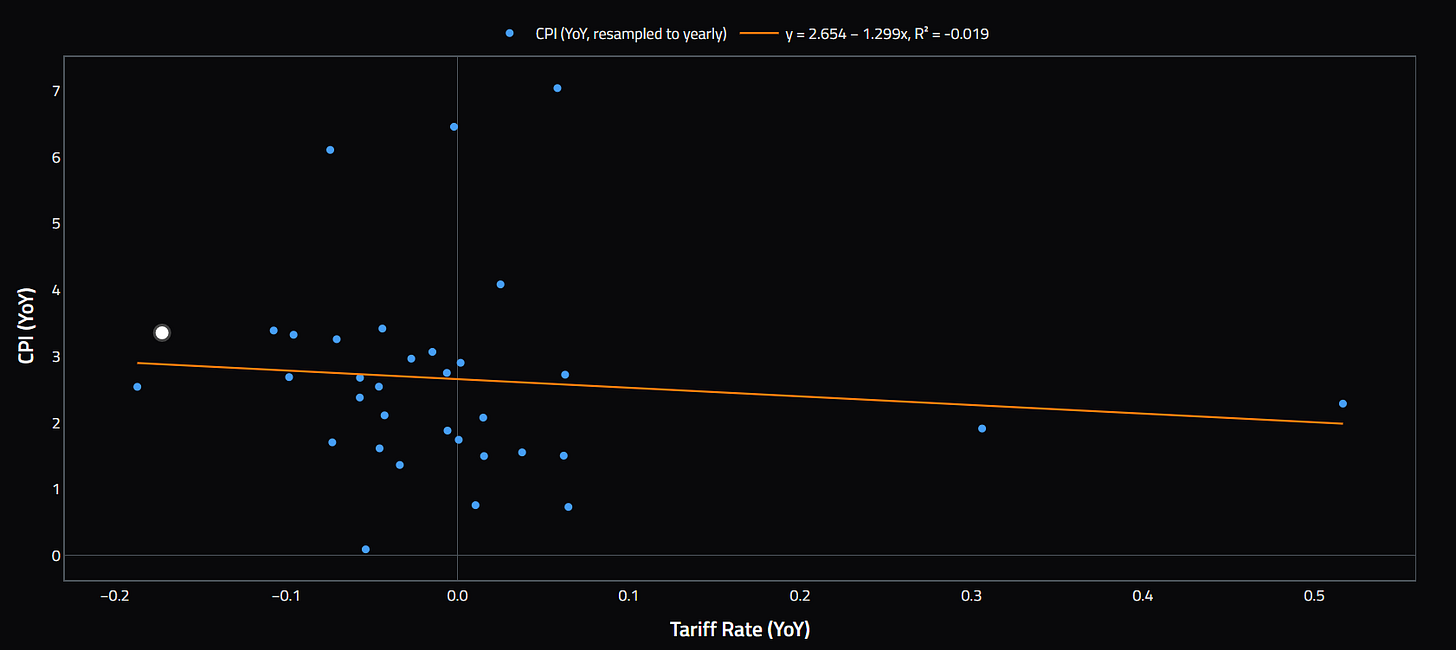

The graphs below illustrate the impact of tariff rate increases on the price level and the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) in the U.S. The graphs set time t=0 as the day when tariff rates are raised.

The first graph shows how the price level, measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) year-over-year (YoY), changes in response to an increase in tariffs. As the data reveals, the average impact on inflation is relatively modest. In fact, the mean increase in inflation tends to be just around 0.5 basis points relative to the start of the period. This suggests that, while tariffs might push prices up in specific sectors, the overall effect on the broader economy’s price level remains quite small.

The next graph illustrates the change in the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) for the U.S. following a tariff increase. On average, we see the REER rise by around 2.5%. This increase in the REER suggests that the U.S. dollar tends to appreciate in response to the tariff hike, which helps reduce the cost of imports and offsets some of the inflationary pressures caused by higher tariffs.

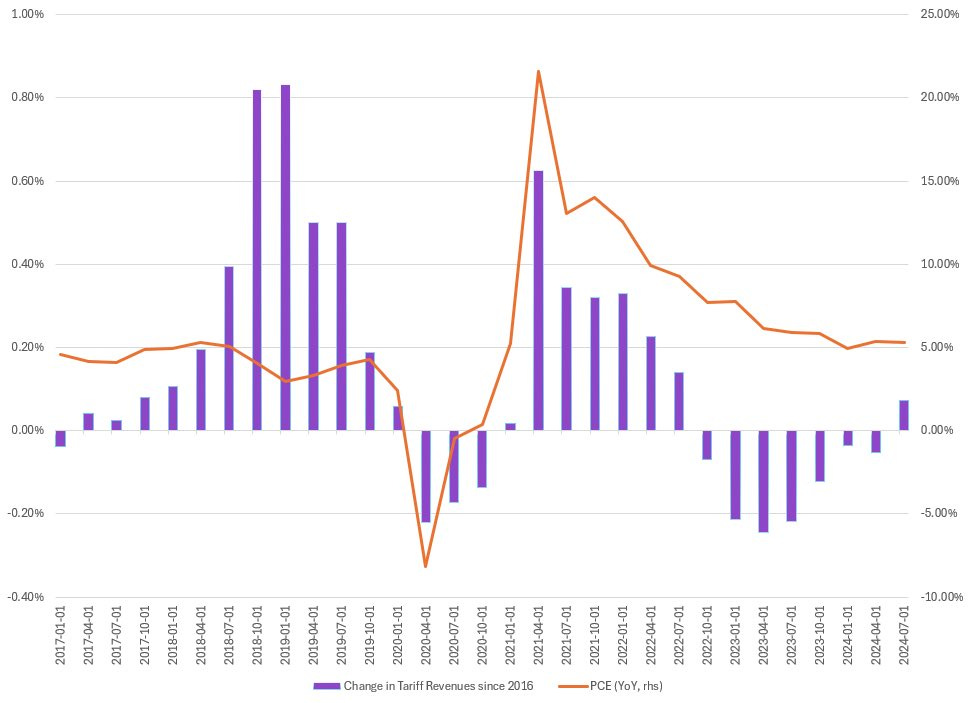

When tariffs were first implemented back in 2016 and 2018, their impact on Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) was minimal. In fact, during those periods, tariffs accounted for only about 30 basis points (bps) of total consumption expenditures. This suggests that tariffs have a relatively small effect on consumer spending, even when they are introduced.

At times, there has been a weak to negative correlation between tariffs and PCE, especially when we look at historical trends. The data suggests that while tariffs may increase prices in specific sectors, they do not significantly influence overall consumption expenditures in the economy. In fact, removing tariffs would likely ease inflation to only a minimal extent and would not have a substantial impact on lowering PCE.

It’s important to note that both imposing tariffs and removing them come with costs. While removing tariffs could theoretically reduce inflationary pressures, the overall impact on inflation would still be limited. The complexity of global trade and production means that the removal of tariffs does not necessarily translate into a significant drop in domestic prices.

Tariffs on specific commodities, such as steel, did cause a brief spike in prices. However, these price increases were typically followed by a subsequent decline as supply chains adjusted and domestic production expanded. This was particularly evident in the case of steel and other commodities, where the initial impact of tariffs was a one-time price increase, but prices eventually stabilized.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the role of tariffs in certain circumstances. The pandemic led to disruptions in global supply chains, but it also underscored the need for domestic production capacity. Tariffs helped encourage the buildout of domestic industries and played a role in the normalization of supply chains. While this was not the primary driver of the recovery, it did emphasize the utility of tariffs in specific scenarios, particularly when national security or supply chain resilience is a concern.

The economics of tariffs is not always straightforward. In some instances, such as during COVID-19, tariffs may have proven useful for strengthening domestic industries and improving supply chain stability. However, in other times, their impact on inflation and economic growth may not be as pronounced. The overall conclusion is that tariffs contribute very little to domestic price increases that influence PCE in a significant way.

Recently, Canada and Mexico were hit with significant tariffs: a 25% tariff on a wide range of goods, and a 10% tariff specifically on oil imports for Canada, while Mexico faces the same 25% tariff increase. The potential economic fallout from these tariffs could be severe for both nations. In this analysis, we’ll use insights from the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) and add assumptions about retaliation and currency movements to explore the effects on inflation, GDP, and domestic economic conditions.

Canada and Mexico are likely to be disproportionately affected by these tariffs due to their strong trade dependence on the United States. As two of the U.S.'s largest trading partners, both countries rely heavily on exports to the U.S. for economic growth.

The anticipated retaliation, combined with currency movements, will exacerbate the situation. For instance, we can expect the USD/CAD exchange rate to range between 1.48 and 1.50 and the USD/MXN exchange rate to hover between 23 and 25. This means that both the Canadian dollar and the Mexican peso are likely to depreciate relative to the U.S. dollar, further complicating the economic situation for these nations.

When tariffs are imposed and retaliation occurs, weaker currencies in Canada and Mexico could significantly raise domestic prices. This phenomenon will likely contribute to higher inflation in both countries. A depreciating currency makes imports more expensive, meaning that goods and services priced in foreign currencies, particularly those sourced from the U.S., will see increased costs.

This currency depreciation will have a much larger impact on domestic inflation in both Canada and Mexico compared to the United States. The U.S. would likely experience less inflationary pressure, especially if the U.S. dollar appreciates due to its safe-haven status. The strength of the dollar could help keep inflation in check within the U.S., offsetting some of the inflationary effects of the tariffs.

The elasticity of the U.S. economy means that the negative impact on U.S. GDP due to the tariffs is likely to be lower than in Mexico and Canada. The U.S. has a more diversified economy and can absorb the impacts of tariffs more effectively, especially compared to smaller, more trade-dependent nations like Canada and Mexico.

Mexico, on the other hand, being an emerging market (EM), is likely to face more significant challenges. The increased cost of imports, particularly intermediate goods that are crucial for production, could undermine economic growth and industrial output. As a result, Mexico is expected to experience a much larger negative impact on GDP than the U.S., in part due to its higher trade dependency on the U.S. market.

In response to these challenges, Canada could be inclined to cut interest rates by 75 to 100 basis points (bps) during an upcoming central bank meeting. The aim of such a move would be to support domestic demand and try to offset the negative impacts on economic growth. By lowering rates, the Bank of Canada could help stimulate spending, borrowing, and investment, ultimately shifting the aggregate demand curve to the right and stimulating economic activity.

On the other hand, Mexico, like many emerging market economies, might raise interest rates in response to rising inflationary pressures. A rate hike could help stabilize the currency and control inflation, but it would also weigh heavily on domestic demand and economic activity. The increase in borrowing costs could dampen consumer spending and investment, further slowing GDP growth in Mexico.

As summarized by economists McKibbin and Noland, the trade integration between the U.S., Canada, and Mexico plays a critical role in understanding the full impact of tariffs. They argue that Mexico and Canada are much more dependent on trade with the U.S. than the U.S. is on them. This makes the imposition of tariffs particularly damaging for these two countries.

The authors point out that intermediate goods, especially in industries like motor vehicles, cross borders multiple times as part of integrated supply chains. Imposing tariffs at each stage of production would disrupt these complex networks, causing severe economic inefficiencies. In their words, the paper notes that such a policy would be "disastrous" for the economies of both Canada and Mexico, as it would lead to higher costs, reduced production, and potential job losses in industries reliant on cross-border trade.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the economic outlook on tariffs is not straightforward. The impact of tariffs on inflation and prices is influenced by a variety of factors, and their effects are not always as significant as they may initially seem.

While tariffs do lead to price increases in specific sectors, historical data suggests that there is often a negative correlation between tariffs and Consumer Price Index (CPI) in the broader economy. This means that, in many cases, tariffs have not had a large impact on overall inflation. One key factor mitigating this effect is the movement of exchange rates. Currency fluctuations, especially the appreciation of the U.S. dollar, can offset the expected rise in prices that would come with higher tariffs, reducing their overall impact on consumer prices.

Additionally, tariffs' impact on inflation is often more muted when considering the global supply chain dynamics. For example, countries and businesses can adjust to tariff changes by sourcing goods from different markets, finding efficiencies, or increasing domestic production, all of which help to alleviate price pressures.

Moreover, while tariffs may have short-term inflationary effects, their long-term influence is less clear. In some cases, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic, tariffs served to promote domestic manufacturing and enhance supply chain resilience, which proved beneficial for the economy. However, in other circumstances, their economic impact may be relatively minor, especially when considering the broader market forces at play.

Ultimately, although tariffs can lead to price increases in certain industries, their aggregate impact on inflation—as measured by CPI—is often limited. The complex interplay of tariffs, exchange rates, supply chain adjustments, and domestic production means that, for most of the time, the influence of tariffs on overall inflation and economic growth is not as dramatic as it may appear at first glance.

The false sense of security that comes with economic models and regressions applied to a completely different environment.

The total level of government debt outstanding is different. The market demand for coupon issuance is different. The fiscal deficits at a level unseen before excluding war times. Geopolitical situation is different. Employment is different. Wage growth is different. The list goes on and on. It’s different not only in the USA but worldwide.

Probably the honest take is that nobody really knows and that inflation is not the inevitable conclusion like most pundits want us to believe. I personally think impact on growth will dwarf inflationary impulse but there are massive fat tails on both sides. This is not 2016.

Great article