Canada is a nation well-known for being the United States' largest trading partner. It has long benefited from its neighbor to the south, but it seems the tide is shifting, putting Canada in an interesting position from a growth perspective. Canada has stopped focusing on productivity and attempting to lower its unit labor costs. Instead, it has used capital to invest mostly in financial assets. This shift has led to a deterioration in the standard of living, but it has also come at the cost of lower economic output for Canada in general. This highlights the differences between the two economies and what this means for Canada and Canadians going forward.

We will first look at Canada's import share compared to other nations. One can see that Canada has largely been one of the largest trade partners with the United States; however, this is now starting to deteriorate for the Canadian economy. Over time, both China and Canada have fallen, and this position has now been taken by Mexico. There are a couple of reasons for Canada's decline that will be discussed next, with unit labor costs being a significant factor.

We will now examine the trend of Canadian trade and unit labor costs. Unit labor cost essentially refers to wages adjusted for productivity. If wages grow but productivity falls, wage inflation occurs, indicating a loss of competitiveness for Canada. Canadian firms become less competitive and more expensive to buy from on the global scale. Given that the United States has the flexibility to change business partners easily, Canada is no longer viable, leading to a shift in trade to areas with a massive boost in productivity and relatively low labor costs. This results in fewer exports for Canada and a declining share of US imports.

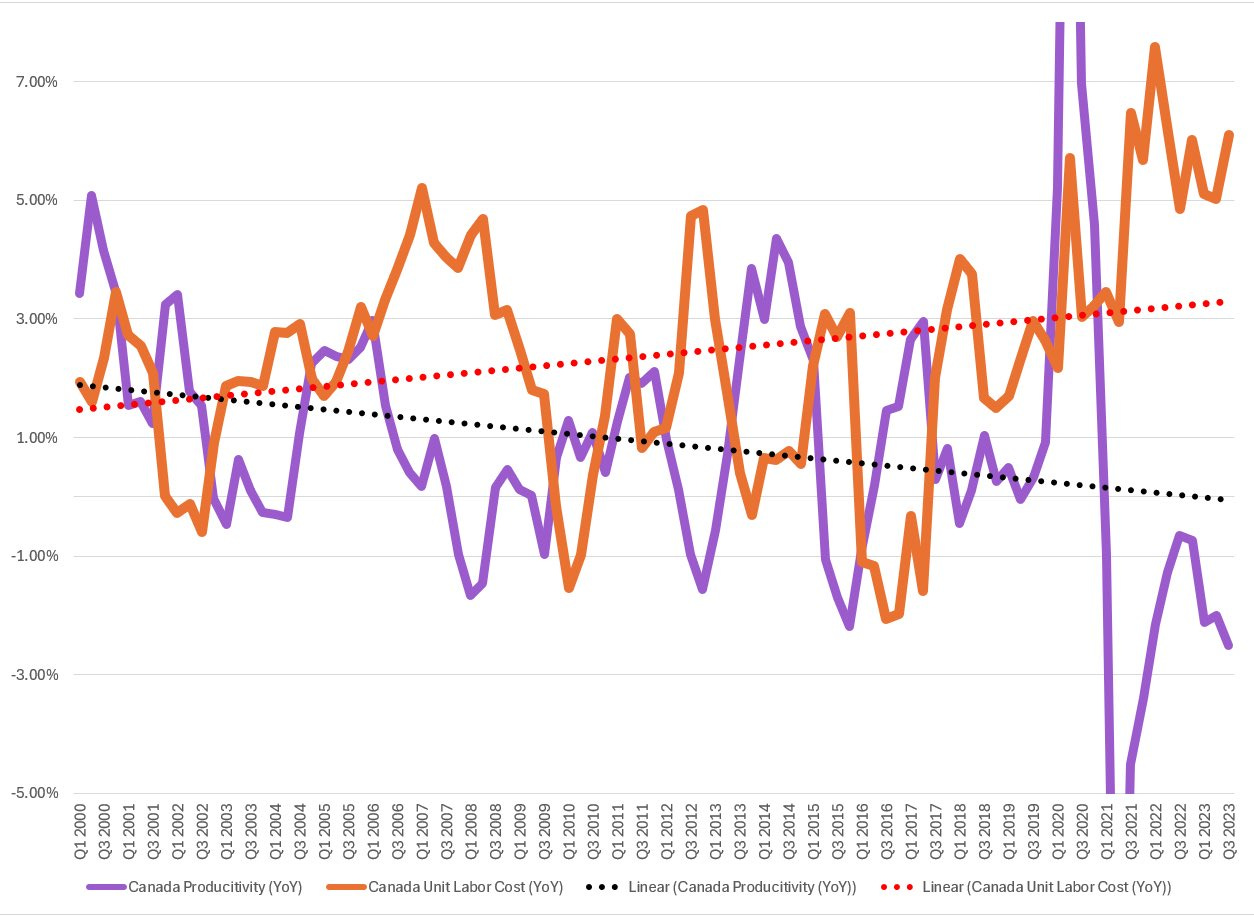

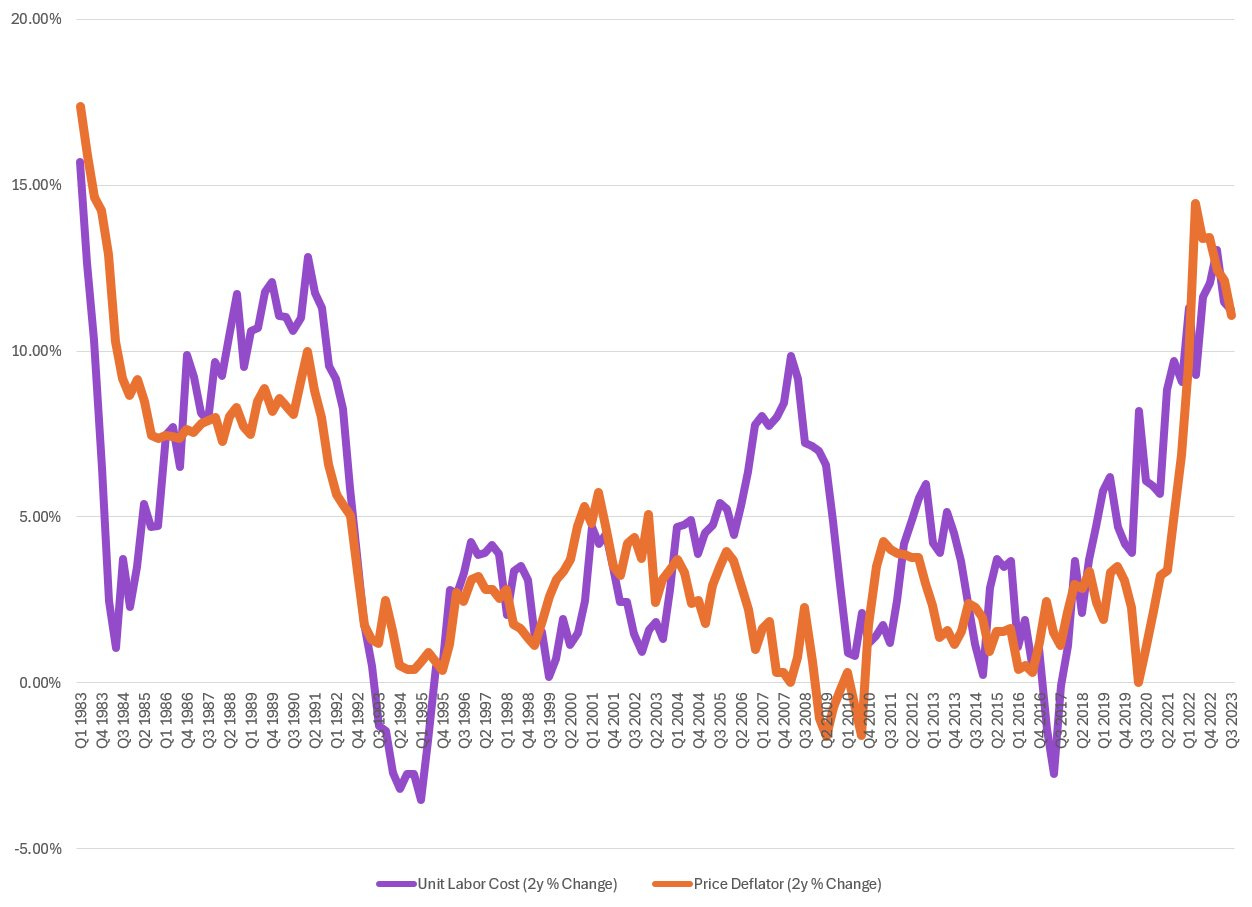

We are witnessing the worst productivity levels for Canada since the beginning of the data series (1981) and the worst unit labor costs since the early 1980s. How did Canada get here? Subsidization of consumption and the financialization of the economy have started to bite. Years of underinvestment have decimated the manufacturing and industrial base, and that capital has now been diverted into financial assets, which are much more liquid than real economic assets. Essentially, for every one dollar invested in financial assets, there is only a 1:1 decline in real economic investment spending. As shown below, this results in skyrocketing wages and productivity at the worst levels on record since data was first recorded in 1981.

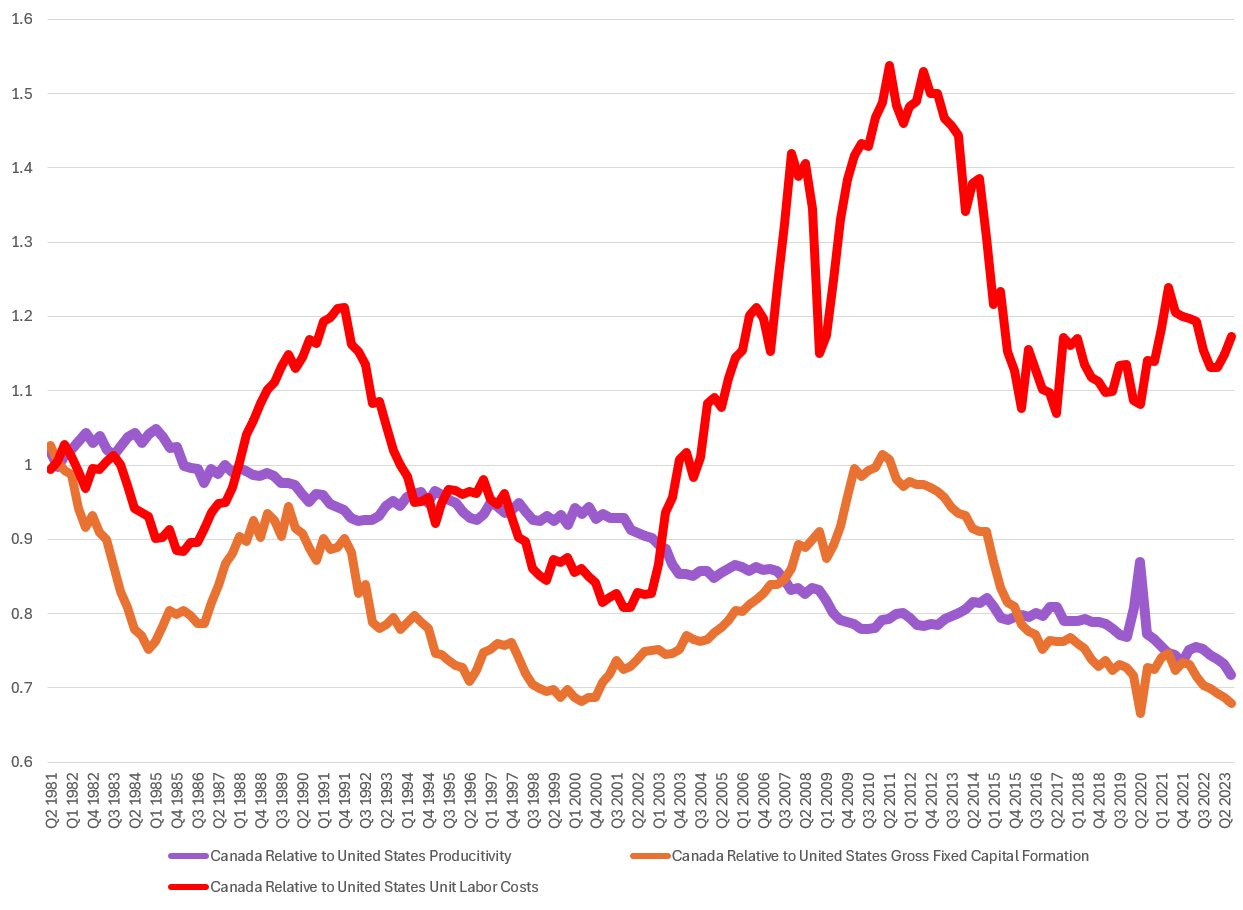

Now, one might be asking what drives productivity. One aspect is greater gross fixed capital formation, which increases productivity. This has a direct impact on employees, as you have more capital per worker, leading to higher levels of aggregate output. Comparing Canada to the US, one can observe that Canada has been investing much less than the United States in gross fixed capital formation, closely following the downward trend in productivity. This has resulted in overall higher levels of unit labor costs for Canada relative to the United States, leading to a loss of its ability to produce output and causing ripple effects throughout the economy.

If Canada truly wants to improve itself, it must increase the amount of capital per worker. Canada faces a problem where the growth rate of new investment (economic assets, i.e., plants, machinery, equipment) is outstripped by the depreciation (consumption) of that capital stock. This means there is a level at which capital consumption is decreasing at an increasing rate, quicker than the decrease in the overall level of the working-age population. This will be a huge constraint on the aggregate level of output, absent a massive shift in investment.

I discussed earlier how lower productivity can lead to further issues within the economy, one of which is stickier inflationary pressures. This can be measured by assessing excess demand, which is quantified using the output gap. To simplify, when you have a positive output gap (any positive number over zero), it indicates demand exceeding current supply, leading to inflation. On the flip side, a negative output gap implies more supply than demand, driven mostly by levels of aggregate output. As mentioned, output is influenced by gross fixed capital formation, which provides more capital per worker.

Observing Canada's rising output gap, it suggests that, contrary to what Tiff Macklem (Governor of the Bank of Canada) says, the Canadian economy still experiences excess demand. Bringing this back into equilibrium will be challenging, particularly as productivity in Canada continues to contract. This contrasts with the United States, where effective supply-side economic policies are driving the output gap towards zero (equilibrium) through massive increases in the level of output.

Canada's lackluster productivity growth is causing structurally higher price growth. Nominal wage growth is not inflationary if it is growing alongside productivity (i.e., unit labor costs). The problem arises when wages grow at a rapid percentage change compared to productivity, which is inflationary. Canada's low productivity growth and high nominal wages have pushed prices to some of the highest levels since the 1980s.

Increases in efficiency and productivity tend to lower prices. In the absence of increases in productivity, unit labor costs will remain high. Without investment to boost productivity, prices will remain sticky, constraining consumption for households and altering the income elasticity of goods, shifting consumption more towards "inferior goods."

The other way in which a reduction in gross fixed capital formation can harm the economy is that it leads to inefficiency. When inefficiency or higher labor costs occur, it reduces the desire for employment. What we are witnessing in the Canadian economy is that declines in gross fixed capital formation are also lowering the rate of employment.

As shown in this chart, if Canada wants to increase the natural rate of employment, a good starting point would be to increase the rate of gross fixed capital investment. As labor becomes less productive, obviously, less labor will be employed, and the cost of labor becomes higher in aggregate. This is what we are currently observing in Canada

.As mentioned, gross capital formation increases productivity through additional capital per worker. This allows more output to be produced, and you can also achieve increases in total factor productivity. This, in turn, leads to additional increases in output, as does the investment in the capital stock. All of this results in overall additional capital per worker, leading to higher levels of output. If the trends of growth continue, and there is a commitment to growing these three variables, even with a declining labor force, you can achieve overall increases in the standard of living.

The problem is that Canada has experienced a long period of negative growth rates in both variables of gross fixed capital formation, which has led to lower levels of aggregate output

With that being said, there also continues to be a long-run divergence between the United States and Canada in terms of total factor productivity (TFP). TFP essentially measures how efficiently inputs are used within the production process. The higher the reading, the more efficient the usage of inputs within the production process. Looking at the chart below, you can see the huge gap between Canada and the United States, with Canada lagging behind massively. When measuring this, we do so on an annual basis because TFP can be quite volatile, so it is better to look on a longer-term basis instead of monthly, quarterly, etc. An annual measurement is a better way to gauge TFP.

A large contributor to this divergence is the negligible investment we have seen, as discussed above in terms of gross fixed capital formation. Since the oil sector was affected around 2010, expenditures on plants, machinery, and equipment have all been trending lower. This has led to a decline in TFP over the last 14 or so years. This has been a significant driver of the reduction in spending on investment, which will be discussed next.

Now, there are a few significant drivers of TFP, and technological advancement is one of those key factors. The more you spend on strategic technological advancement, the higher the rate of TFP. This is due to the fact, as mentioned above, that if you utilize technology to more efficiently combine inputs to produce increased levels of output, TFP will grow. The problem is that Canada has not been doing that.

Canada has some of the lowest levels of R&D spending as a percentage of GDP, well below the OECD average. The OECD average in 2021 was 2.718% of GDP, while Canada's R&D spending at that time was 1.697% of GDP. This means Canada was 1.021% lower than the OECD average. The US, during that time, allocated 3.457% of GDP to R&D, which was 0.739% higher than the OECD average, and the US was 1.76% higher than that of Canada. This could be a significant driver of TFP, and Canada is missing out on R&D that could help advance certain sectors within the country.

Below, there is also a chart looking at investment in technology as a % of GDP relative to TFP. One can see that they are somewhat correlated on an annual % change basis. When investment in technology grows, it tends to have a direct impact on TFP through the mechanism, as mentioned, of increasing inputs to more efficiently produce output.

However, the problem has now become that Canada is not interested in these kinds of investments. This not only harms Canadian businesses but also affects the overall employees, as less capital will be utilized in the production process, and more labor will then have to fill in for the role of capital. This is another contributor, as mentioned in the beginning, to higher unit labor costs. Utilizing labor instead of capital in a nation that is pretty capital-intensive reduces the level of aggregate output.

Finally, on something relevant to the comments from Tiff Macklem today that they do not think now is the time to talk about interest rates, the neutral rate of interest, also known as R*, disagrees with him. The neutral rate is not pointing to "higher for longer" for the Canadian economy but lower, much, much lower, currently sitting at under 1.8%. The reason for this can largely be explained by the factors discussed above, one of which is productivity. As the graph below shows, as the United States' productivity increases relative to that of Canada's, the spread of the neutral rate is widening for the US, meaning the neutral rate of interest is much higher than that of Canada's. This is because higher productivity growth, in general, increases the demand for capital relative to the supply of loans (in theory), and as a function of that, pushes up the neutral rate of interest.

You also get higher levels of growth in the United States relative to Canada, given the things we are seeing on the supply side, which also pushes up the neutral rate of interest. When the economy is seen as sluggish or when growth and investment are weaker, it will be a constraint on a higher R*. Canada has had, for a long time, as can be seen throughout this article, very sluggish productivity growth, coupled with declining demographics and an aging population, which slows workforce growth, all constraining a higher R*. Usually, forecasting productivity growth is difficult, and thus you can see somewhat changes in estimates of the R*. However, given the almost decade-long decline for the Canadian economy, absent a massive overhaul and fiscal supply-side spending, it is a safe bet to believe the neutral rate of interest is much lower for Canada. Given these factors, we can even see how aspects that might seem unrelated to interest rates, like productivity, TFP, and demographics, can actually be a constraint on interest rates.

With all this being said, this is not supposed to be purely negative; it's a piece to highlight what Canada should be doing differently. Focusing on supply-side economic policies and trying to bring back real capital investment is something all levels of government should be prioritizing. As an American currently living in Canada, I can see the huge impact supply-side economic policies have had on growth within the United States, and I believe this is something levels of government should be discussing in Canada. This would not only benefit Canada but also improve the lives of Canadians through higher standards of living in the long run.

I am a firm believer in the Solow Growth model, where continual increases in TFP, capital stock investment, etc., lead to long-run increases in the standard of living. This is something Canada should be focused on and committed to; otherwise, future growth outlooks remain relatively weak going forward.

Good if sobering article.

Canadian politics seems to focus on games about perception with corruption in the background. I'm really not hopeful either party will make the long term (multiple term) investment and policy commitments necessary to deliver real growth.

Anecdotally people I know who own businesses seem to think "growth" comes from exploiting foreign labour or cheap immigrant labour. The Canadian mindset doesn't seem to contain real productivity growth, only scams, loopholes and the like.