Introduction

Lately, headlines, social media chatter, and even academic papers have been buzzing with speculation about the decline of the U.S. dollar. From trade invoicing to cross-border settlement, the mechanics of global commerce can be opaque—and often misunderstood. Terms like "invoicing" and "settlement" are frequently used interchangeably, fueling confusion and misinterpretation. Some argue that a falling share of dollar-denominated settlement signals the end of the dollar’s dominance. Others point to its continued strength in invoicing as proof that its status remains unchallenged. Meanwhile, new trade blocs are forming, and alternative currencies are being proposed, all with the aim of reducing reliance on the greenback.

This post dives deep into the facts and fiction behind the dollar’s role in global trade, demystifies the complex terminology, and examines whether we’re truly witnessing the beginning of a post-dollar world—or just another cycle of hyperbole.

Everything you will read below is summarized from the ECB article “Global Trade Invoicing Patterns: New Insights and the Influence of Geopolitics” by Anja Bruggen, Georgios Georgiadis, and Arnaud Mehl, published in June 2025. I have summarized the report here because it presents the data on invoicing more clearly than I could. After this summary, I will share my own analysis and data to demonstrate that we are not witnessing a decline in the dollar.

Trade Invoicing

The choice of invoicing currency in global trade has significant effects on how countries experience exchange rate shocks and how effective their monetary policies are. Traditional models like the Mundell-Fleming assume exporters price goods in their own currency, meaning depreciation boosts exports by making them cheaper abroad. However, newer models highlight “dominant currency pricing,” where most global trade is invoiced in major third-party currencies—primarily the U.S. dollar—regardless of trading partners. This weakens the expected benefits of exchange rate adjustments, as pricing in a dominant currency like the dollar often renders depreciation ineffective in boosting exports.

China’s rise in global trade raises the possibility of a shift toward renminbi invoicing. The country has actively pushed for international use of its currency by encouraging renminbi settlements, creating central bank swap lines, and easing capital restrictions. Still, despite changes in trade flows and policy, dominant currency usage tends to persist unless large-scale coordinated shifts occur.

Geopolitical developments—like the sanctions on Russia—have further fueled interest in alternative payment systems and reduced reliance on Western currencies. However, tracking shifts in invoicing practices is difficult due to limited data availability. Standard international trade databases typically lack currency-specific invoicing data. Customs records could offer insights, but data collection is inconsistent across countries and not always shared with central authorities.

To improve visibility, the IMF and ECB have compiled a new dataset covering trade invoicing currency patterns for over 120 countries from 1990 to 2023. This effort expands previous research and includes more emerging markets and renminbi usage, offering deeper insights into evolving trends in global trade currency preferences.

Trade Invoice Patterns

The updated data through 2023 shows that the U.S. dollar and the euro continue to dominate global trade invoicing. Around 40% of global exports are invoiced in dollars—far exceeding the share of exports actually destined for the U.S.—underscoring the dollar’s global role beyond just commodity trade. The euro's invoicing share is similarly high, reflecting the euro area's greater trade openness. However, unlike the dollar, the euro’s invoicing share more closely aligns with the share of exports going to euro area countries, suggesting its influence is more regionally concentrated.

The updated data reinforces that the U.S. dollar remains the dominant global vehicle currency for trade invoicing, widely used by countries regardless of their direct trade with the U.S. In contrast, the euro’s use as a vehicle currency is much more regionally concentrated, primarily limited to Europe and parts of Africa, highlighting its more localized influence in global trade.

The latest data shows that despite geopolitical shocks like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the use of the U.S. dollar and euro in global trade invoicing has remained remarkably stable. While the share of global exports going to the U.S. and euro area has declined since 2000—reflecting their shrinking share of global output—the dominance of their currencies in trade invoicing has not diminished.

The new data reveals that while the renminbi's share of global trade invoicing has been gradually increasing, it remains very low overall. Despite China’s significant rise in global exports since joining the World Trade Organization in 2001, the share of global exports invoiced in renminbi has remained minimal, with only a small increase after 2022, which is hardly noticeable on a global scale.

Renminbi invoicing has grown more noticeably in specific regions like Asia-Pacific and parts of Europe, but it still represents less than 2% of global exports. In Asia-Pacific, its use began increasing around 2010, while in other parts of the world, adoption remained negligible until 2018. Since then, it has picked up in some areas, including Europe and the Western Hemisphere, though it still accounts for less than 1–2% of exports in each region.

Change in Invoicing

Geopolitical tensions are increasingly influencing trade invoicing patterns by altering global trade networks and raising the costs or risks associated with using dominant currencies like the U.S. dollar or euro. Standard models suggest exporters choose invoicing currencies based on price stability in the face of future demand and input cost shocks. However, in a fragmented global trade environment—where blocs form due to tariffs, sanctions, or geopolitical alignments—exporters may shift away from dominant currencies toward alternatives that better reflect their trading partners and geopolitical ties.

Additionally, while traditional models assume that invoicing and settlement currencies are the same, sanctions and restrictions may make it impractical to settle payments in a certain currency, prompting exporters to switch invoicing currencies as well. Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there has been a surge in alternative payment infrastructures—like Iran’s and Russia’s domestic systems, China’s CIPS, and the proposed BRICS Clear initiative—designed to reduce reliance on Western-led systems.

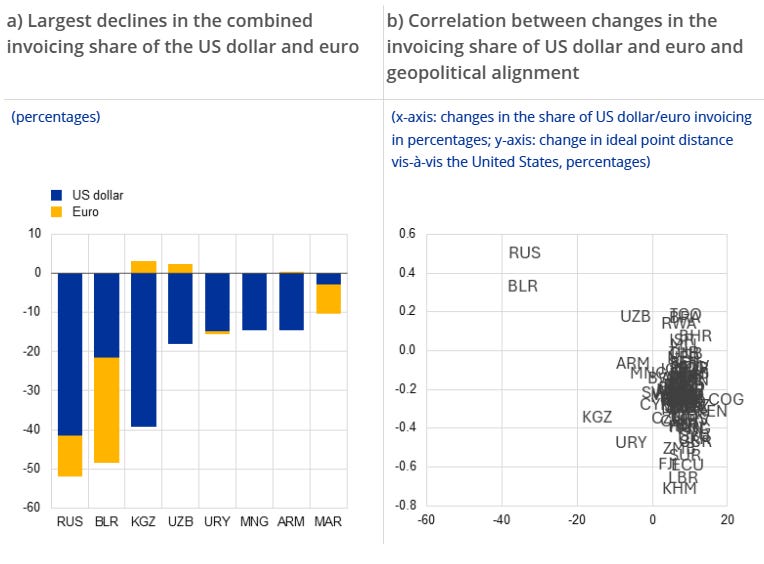

Despite these shifts, recent data from the ECB and IMF show only limited evidence of a widespread change in invoicing behavior linked to geopolitical alignment. The most notable declines in dollar and euro invoicing occurred in countries directly affected by Western sanctions—such as Russia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan—with Russia seeing its combined use of the dollar and euro halved by 2023.

While changes in invoicing currency patterns can be influenced by factors like trade composition, exchange rates, and commodity prices, recent analysis finds that shifts away from the U.S. dollar and euro still correlate with declining geopolitical alignment. However, this relationship is relatively weak. Once countries most directly affected by sanctions—Russia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan—are excluded, the statistical link between geopolitical divergence and invoicing shifts disappears, suggesting that such changes are not widespread and may be concentrated in a few exceptional cases

In summary, despite increasing geopolitical tensions, global trade invoicing currency patterns have remained largely stable, reflecting strong lock-in effects and network externalities driven by complex global supply chains and coordinated pricing behavior. However, future large-scale shocks or structural shifts could rapidly change these patterns, especially if governments actively promote alternative invoicing currencies. Continuous monitoring is essential to detect any tipping points that might lead to significant changes in global trade currency use.

More Proof the Dollar’s Dominance in Global Trade Isn’t Going Anywhere

The following analysis has been compiled by me and presents my perspectives on the topic.

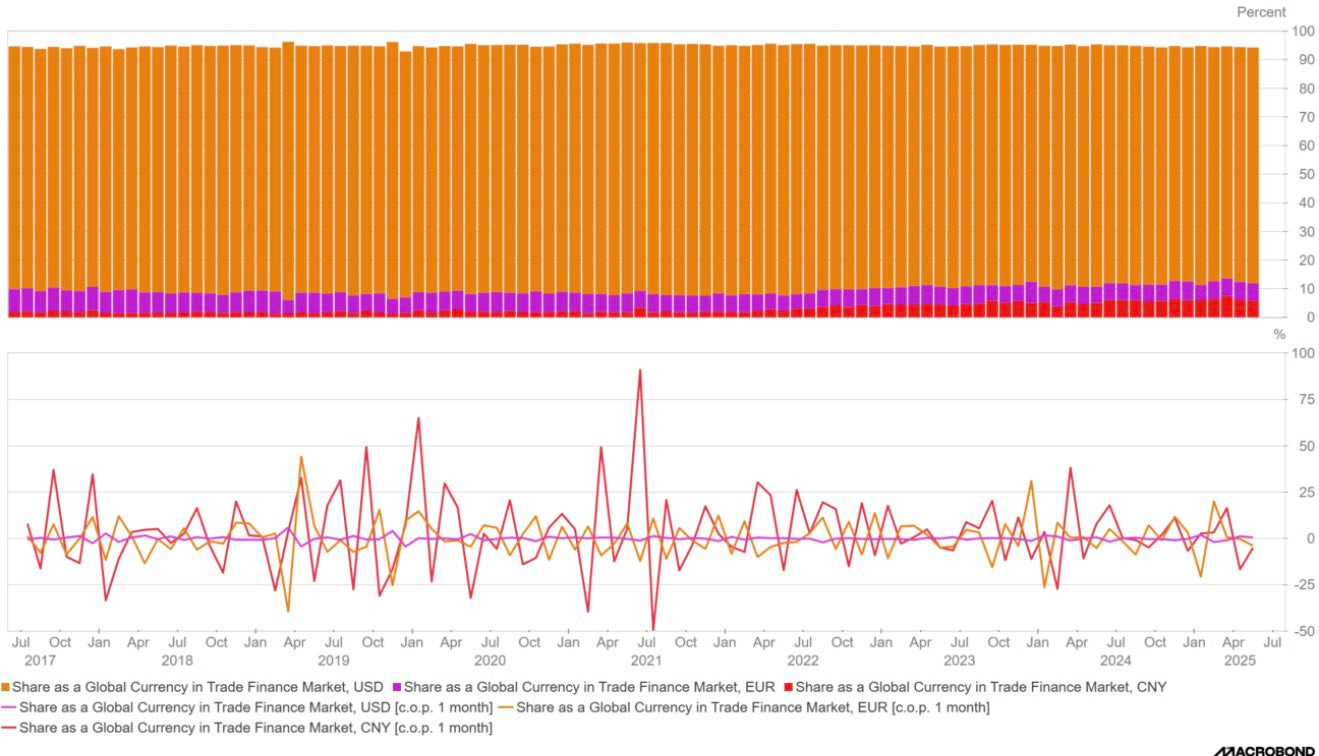

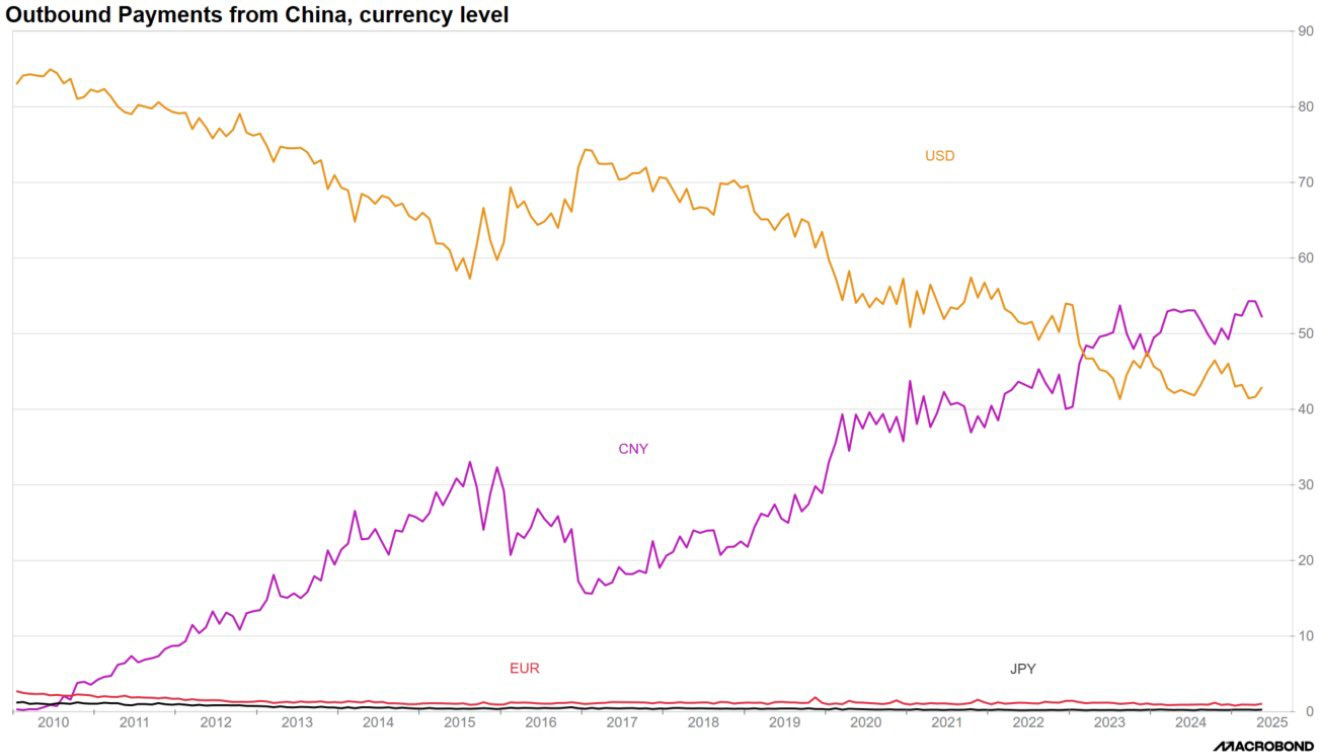

The dollar remains dominant and is currently the only currency showing month-over-month growth. The fact that the vast majority of invoicing and settlement is still conducted in dollars is a clear rejection of the narrative suggesting a decline in the dollar’s role in global trade. We have seen a rapid decline in China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS), as well as a drop in its use in trade finance. Lenders extend credit to facilitate the cross-border movement of goods and services. This reduction indicates a decrease in the utilization of the Chinese yuan in trade.

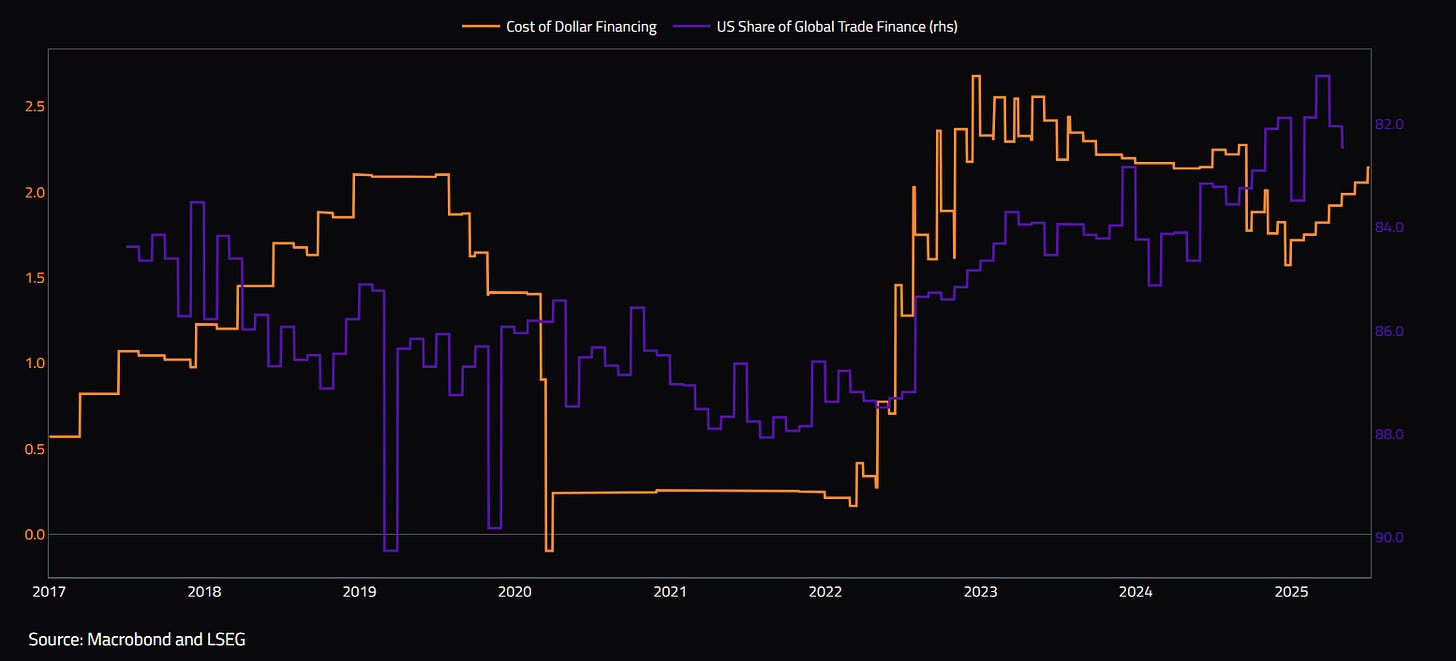

Earlier, the decline in the U.S. share of global trade finance was driven by the rising cost of dollar financing. As that trend reverses, we should expect to see the dollar’s share rise once again.

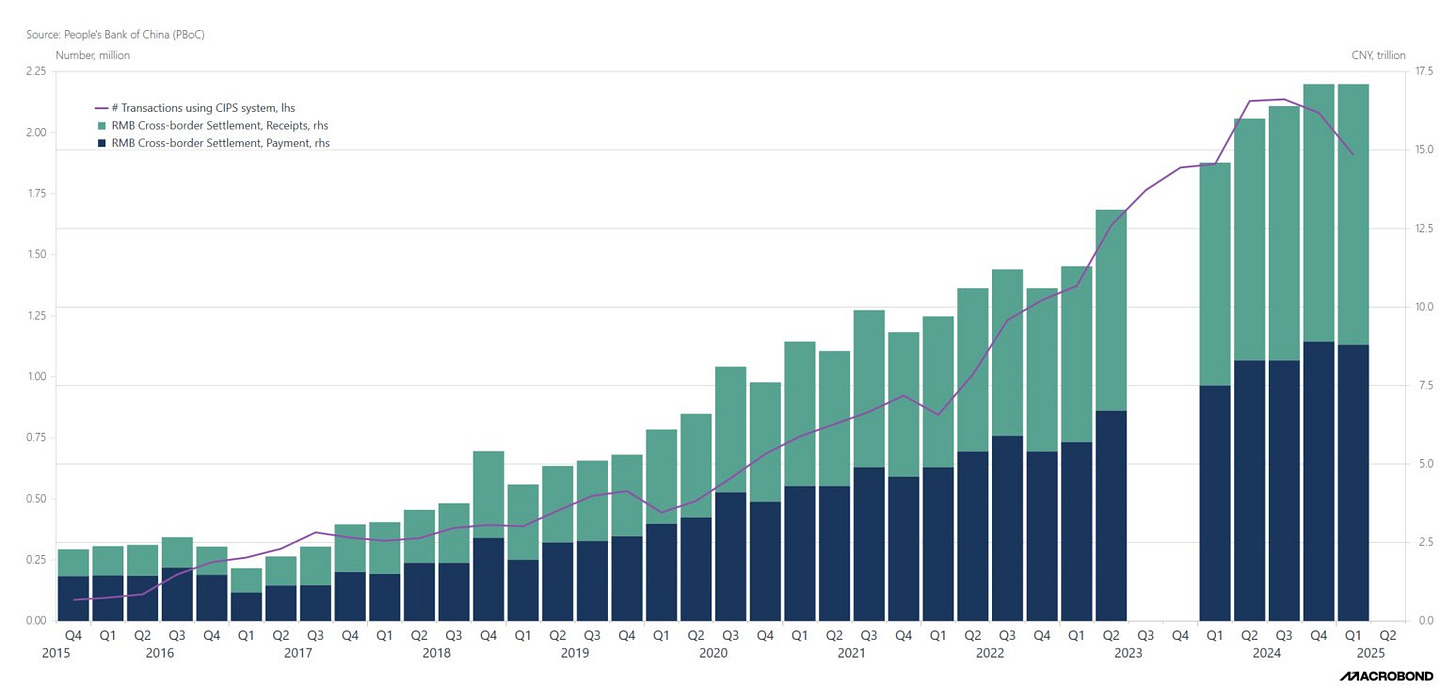

While the rise of China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System (CIPS) once signaled momentum for the renminbi in global trade, recent data suggests that growth may be plateauing—or even reversing (down -10% since peak). After years of steady increases in transaction volumes and RMB settlement, the first half of 2025 shows a clear decline in CIPS usage.

This shift raises important questions about the long-term viability of the renminbi as a global trade and settlement currency. Rosen (2022) notes, Russia began accepting renminbi for oil and coal exports to China in April 2020—likely via CIPS—but this shift was more pragmatic than strategic. The renminbi allowed Russia to continue bilateral trade with China, yet it remains constrained by capital controls and limited convertibility.

Rosen highlights that, initially, Russia preferred euros over RMB for settling trade, underscoring the broader liquidity and utility advantages of the euro. The decline in CIPS transactions may signal that, absent further financial liberalization or geopolitical shocks, the RMB’s global role could remain narrow and regional—far from replacing the dollar as the dominant currency in global trade.

The share of CNY in all cross-border transactions conducted by Chinese non-bank entities with foreign counterparties was virtually zero two decades ago but has since risen to around 55%. In contrast, the U.S. dollar's share, which once stood at approximately 80%, has declined to about 45%. However, recent trends show a reversal: the CNY's share is now falling, while the use of the U.S. dollar in these transactions is rising again. Ultimately, it's about the rate of change. This decline in CNY usage also aligns with the earlier graph, which shows a drop in CIPS transactions and a broader reduction in RMB clearing and settlement services for cross-border payments.

The US dollar still remains dominant currency in swift payments, and if we look closer at China after peaking at 4.33% of total it has now decline down to 2.89%.

Looking at the composition of global international reserves on a quarter-over-quarter basis, we have seen an increase in holdings of U.S. dollar reserves and a reduction in holdings of CNY reserves. The dollar remains close to the 60% mark of total foreign exchange reserves, signaling a reversal in the previous trend of diversification away from the dollar and a slowdown in the rise of non-traditional reserve currencies.

Conclusion

Despite the growing narrative around de-dollarization and the rising use of alternative currencies like the renminbi, the data tells a more nuanced story. While the CNY has gained ground in certain bilateral trade relationships, especially during periods of heightened geopolitical tension, its broader adoption appears to be stalling. The recent decline in CIPS transactions, shrinking CNY usage in cross-border trade, and the stabilization—if not resurgence—of the U.S. dollar’s role in global reserves and trade finance suggest that the dollar's dominance remains resilient. As global financial conditions shift and dollar funding costs normalize, we are already seeing a reversal of previous diversification trends. For all the noise about alternatives, the U.S. dollar remains the central pillar of the global financial system—and for now, there is no clear replacement on the horizon.