China Weakening and The Liquidity Trap

China has been prominently featured in recent news due to its challenges in reviving economic growth. The cautious reopening, coupled with struggles to stimulate consumer spending, has prompted concerns about the country's current situation. China is persistently working to decrease interest rates in an attempt to boost consumption, which has thus far shown limited results. The nation has also faced significant issues such as poor retail sales, liquidity traps, and productivity challenges. Given these circumstances, there is uncertainty about what lies ahead for China's future.

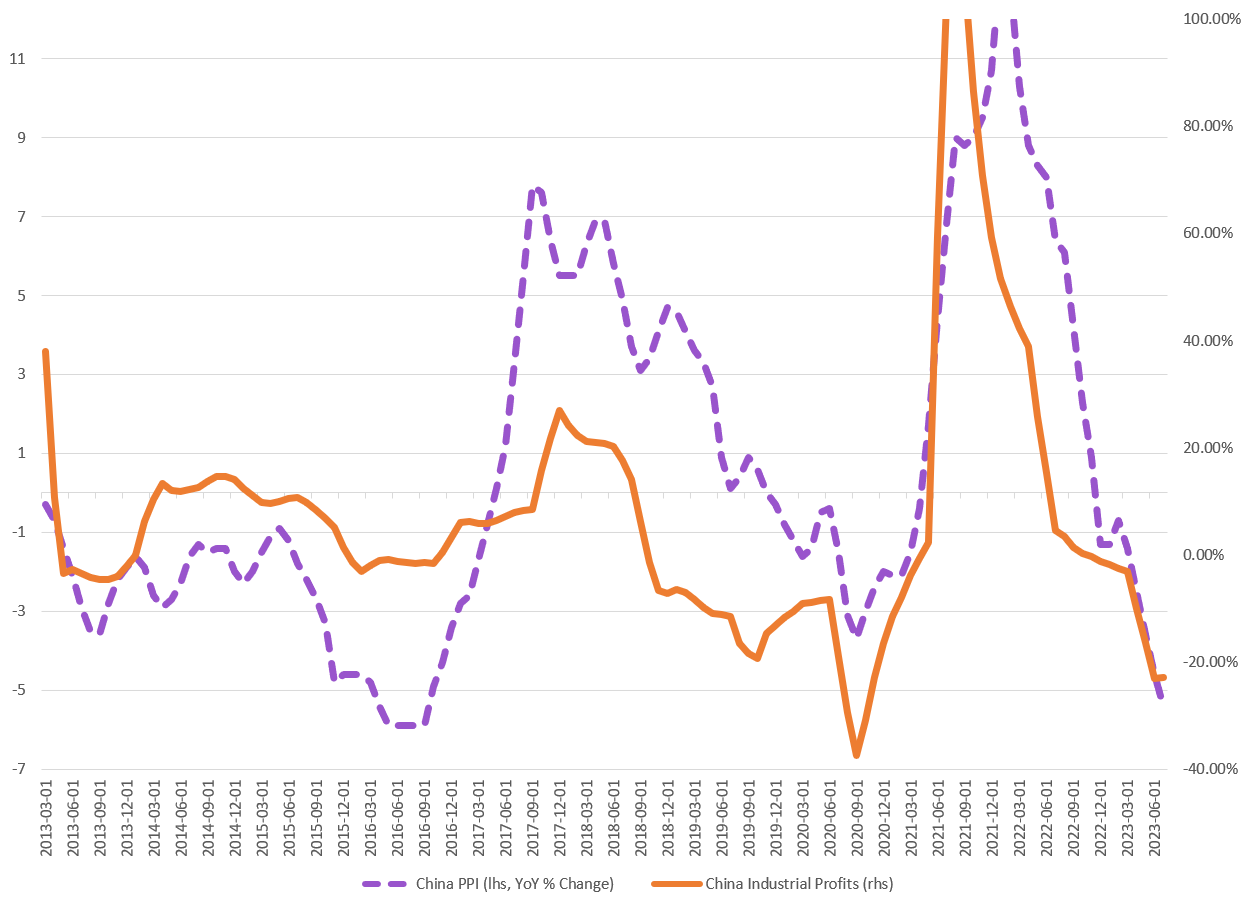

The primary aspect under scrutiny is China's current deflationary trend. The nation is presently grappling with deflation, which is exerting downward pressure on the pricing leverage of Chinese enterprises. During the COVID-19 pandemic and the period when China had imposed closures, the country could, based on the dynamics of supply and demand, enact higher pricing for manufacturing and industrial products. However, this phenomenon has waned, and with supply chains returning to more standard levels, China is losing this capability. As deflation takes root and the aforementioned capacity to raise prices diminishes, Chinese companies are grappling with a substantial impact on their year-over-year industrial profit figures. Consequently, this situation is likely to result in subdued growth within the manufacturing and industrial sectors, and any potential revenue augmentation for publicly traded firms. The knock-on effect is expected to translate into diminished overall earnings growth, with ramifications extending to selling activities within the Chinese equity markets.

Another complicating factor exacerbating deflation is the issue of a weakened currency. China is in need of reestablishing control over its currency's value. Presently, there is an ongoing depreciation of the yuan, driven, it seems, by disparities in the differentials between USD - CNY forward rates. This particular dynamic has contributed to the depreciation of the yuan, and if China persists in implementing policies aimed at easing economic conditions, this trend could be further intensified. The outcome of such a trajectory would likely involve continued devaluation of the yuan, which, in turn, could lead to capital outflows or capital flight from China. This is an observable phenomenon at present, as evidenced by a Reuters article situated adjacent to the aforementioned differentials in relation to the yuan. In recent economic data, we observe that foreign institutions held only 3.24 trillion yuan in bonds traded on the interbank market, a decrease from the previous month's figure of 3.28 trillion yuan. This corresponds to a month-over-month decline of -1.22%, as illustrated below.

As briefly mentioned earlier, the fragility of the Chinese economy has prompted investors to divest themselves of certain Chinese bonds. Furthermore, we are observing a general negative trend in aggregate capital flows. China is experiencing substantial capital outflows, a pattern historically correlated with shifts in the strength or weakness of its currency. The depreciation of the yuan is aligned with more pronounced capital outflows, as investors opt to explore more appealing opportunities beyond China's borders. If China remains unable to halt the exodus of capital, this situation could significantly impede its economic growth trajectory and necessitate additional stimulus measures to foster GDP expansion

Speaking of the necessity for additional stimulus measures to promote GDP growth, there is a notable emergence of a liquidity trap scenario in China. What does this signify? China's efforts to lower interest rates with the aim of invigorating economic expansion are yielding limited results. The situation entails that a more lenient monetary policy is not translating effectively into increased consumer spending. This challenge is compounded by China's existing tendency towards a relatively high marginal propensity to save. In essence, the Chinese population tends to save a significant portion of their disposable income. Despite China's endeavors to reduce interest rates, they are encountering difficulty in driving up consumption levels.

In conjunction with the aforementioned dynamics, China has also been employing foreign exchange (FX) forwards, involving the purchase of yuan, as a means to safeguard its currency. Notably, both the accommodative monetary policy and the utilization of FX forwards have yielded restrained impacts. For reference, the image below provides an overview of China's present rate environment. The country has implemented reductions in basis points for both medium-term loan rates and deposit rates.

Continuing from the brief discussion above, let's delve into the relationship between short-term rates and changes in the Marginal Propensity to Consume (MPC). Examining this period, a notable trend emerges: even as short-term rates experience declines, the MPC is also diminishing. It's important to note that the MPC can indeed be negative, as evidenced in this context, although an in-depth exploration of this topic isn't within the scope here.

Remarkably, the MPC has turned negative, which underlines China's struggle to stimulate consumption through the mechanism of lowered interest rates. In economic theory, this scenario indicates that when consumption remains subdued, savings tend to increase. Essentially, this paints a picture where despite the presence of low interest rates, savings are on the rise, and consumption is lacking. This aligns with the classical definition of a liquidity trap.

Expanding upon the concept of the liquidity trap and the subsequent actions taken by the People's Bank of China (PBoC), it seems that these measures could potentially exert additional constraints on China's economic landscape. It's evident that China's efforts towards stimulus are yielding notably weak results, with a concurrent lack of robust loan demand. This dynamic could potentially engender heightened instability within the financial system, as it may give rise to the formation of asset bubbles. Curiously, it appears that this is currently the path China is inclined to pursue. The nation seems intent on driving interest rates down sufficiently to foster economic growth and simultaneously promote asset expansion.

In the graph provided below, a historical relationship between liquidity injections and yields on Chinese government bonds is discernible. What adds to the intrigue is the complete breakdown of this relationship over the past two years. Although PBoC's easing endeavors are causing yields to decline, the expected response of higher rates when tightening measures are implemented is no longer observable. This brings us to the crux of the thesis: China's liquidity trap is becoming increasingly pronounced.

When the private sector's willingness to borrow wanes, it results in the release of financial sector liquidity. As banks seek returns on these funds, and given the retreating demand for loans from the private sector, the public sector becomes the sole source of appetite for loans. This dynamic elucidates the outsized reaction of the Chinese currency and bond markets to minor adjustments in monetary policy; any excess liquidity introduced now primarily flows into public sector debt. Consequently, the liquidity trap is progressively constricting around the PBoC. Each passing day sees the central bank's influence wane, eventually resulting in the loss of its capacity to stimulate growth.

A significant portion of the previous paragraphs draws from Leith van Onselen's insights, which first highlighted the subdued impact of liquidity injections and their relevance to the liquidity trap thesis.

Let's now turn our attention to loan demand. Central Bank Data is revealing a pronounced deceleration in the realm of overall financing. A comprehensive gauge of credit expansion has slowed notably. Once more, this data serves as a harbinger of the expanding presence of a liquidity trap. It's evident that despite the PBoC's efforts to lower interest rates, the desire for credit remains conspicuously absent.

This scenario highlights the challenge in utilizing lower rates as a means of stimulating economic activity. Strikingly, the sole net borrower in this context persists as the government itself. This amplifies the notion that the private sector's reluctance to engage in borrowing is contributing to the deepening liquidity trap.

Some argue that China's situation is manageable, citing their accumulation of gold reserves. However, this perspective is somewhat inconsequential. Gold represents less than 4% of their total reserve holdings, indicating that China is not significantly bolstering its gold reserves or attempting a significant shift away from the dollar. Furthermore, the relatively modest amount of gold reserves held by China would have limited impact in addressing their current predicament. It's important to recognize this aspect, but it's not a substantial factor in their current situation.

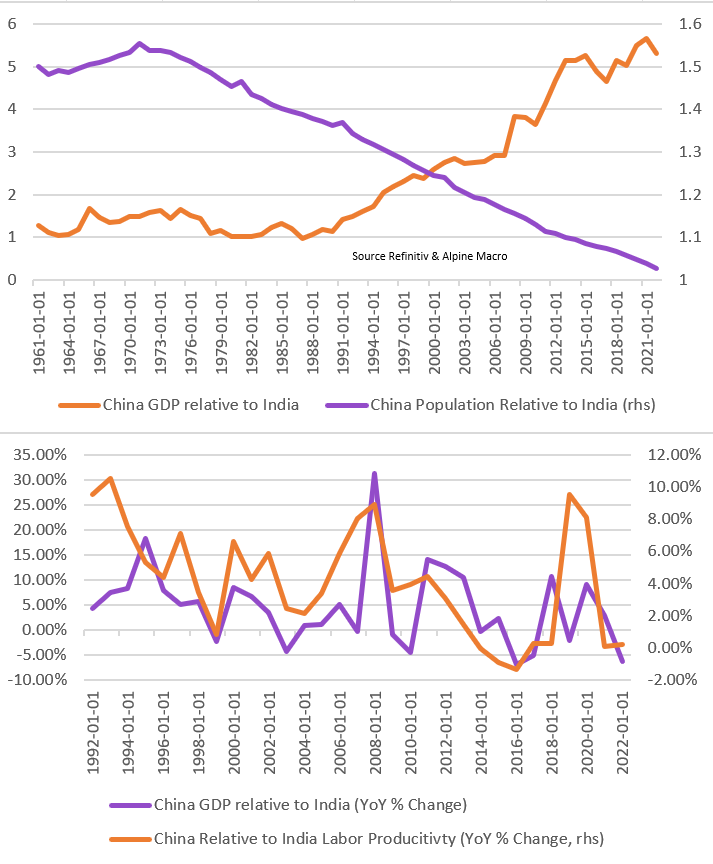

To illustrate the stark weakness of China's recent data, let's compare it with one of its emerging market counterparts, India. Notably, India's population, once significantly smaller than China's, has now substantially closed the gap. Although China's economy remains roughly five times larger than India's, we are witnessing a gradual shift in growth dynamics that slightly favors India. Moreover, India's labor productivity growth rates have begun to outpace those of China. This implies that India's nominal output, adjusted for purchasing power parity, is increasing at a faster rate. Presently, India generates around $8.67 worth of nominal output per hour, while China stands at roughly $13.

China's economy is now encountering dis-economies of scale, with signs of weakening output. Conversely, India's trajectory appears to be on a growth trajectory. I anticipate that within the next 5-10 years, India could achieve nominal output levels surpassing those of China. This situation underscores the persistent issue: when private sector demand for loans remains stagnant and the primary borrower is an inefficient government, it leads to a decline in the private sector's capital stock. This, in turn, triggers diminished levels of output and productivity.

China's struggle lies in its challenge to rejuvenate a private sector that has been declining over a prolonged period. On the horizon, India emerges as a potential heavyweight contender in the global economic arena, but that discussion is best reserved for another occasion.

In summary, the prevailing situation in China is one of increasing desperation to jumpstart its economy. The nation is grappling with an expanding liquidity trap, signifying that its era of robust economic growth is waning. This struggle isn't confined to specific sectors like manufacturing and industrials; it's permeating the entire economy, with the exception of the private sector. The dynamics indicate that China is undergoing rapid diseconomies of scale.

The nation's future outlook for the next 5-10 years appears unpromising, with the odds favoring other countries in the region over China. Despite the post-COVID lockdown reopening, China's economic rebound has been feeble, leaving investors searching for signs of resurgence. Unfortunately, such signs are elusive. The persistent devaluation of the currency and the continual outflow of capital are ongoing challenges impacting the entire capital markets landscape. As things stand, it's becoming evident that rising players like India might be the emerging powerhouse that garners attention, as China's fortunes appear to be on the decline.