Oh Canada???

There has been considerable confusion regarding the economic cycle in Canada. Many people anticipated that during the rate hike cycle, economic growth and activity in Canada would slow significantly. Several factors were pointed to as potential indicators of this negative outlook, including interest rate hikes, nominal consumption, and GDP per capita. However, these metrics have not provided a clear picture of where we stand in the Canadian economic cycle. Given the current dynamics, I would like to revisit the data and discuss the current outlook and my perspective on where things are headed.

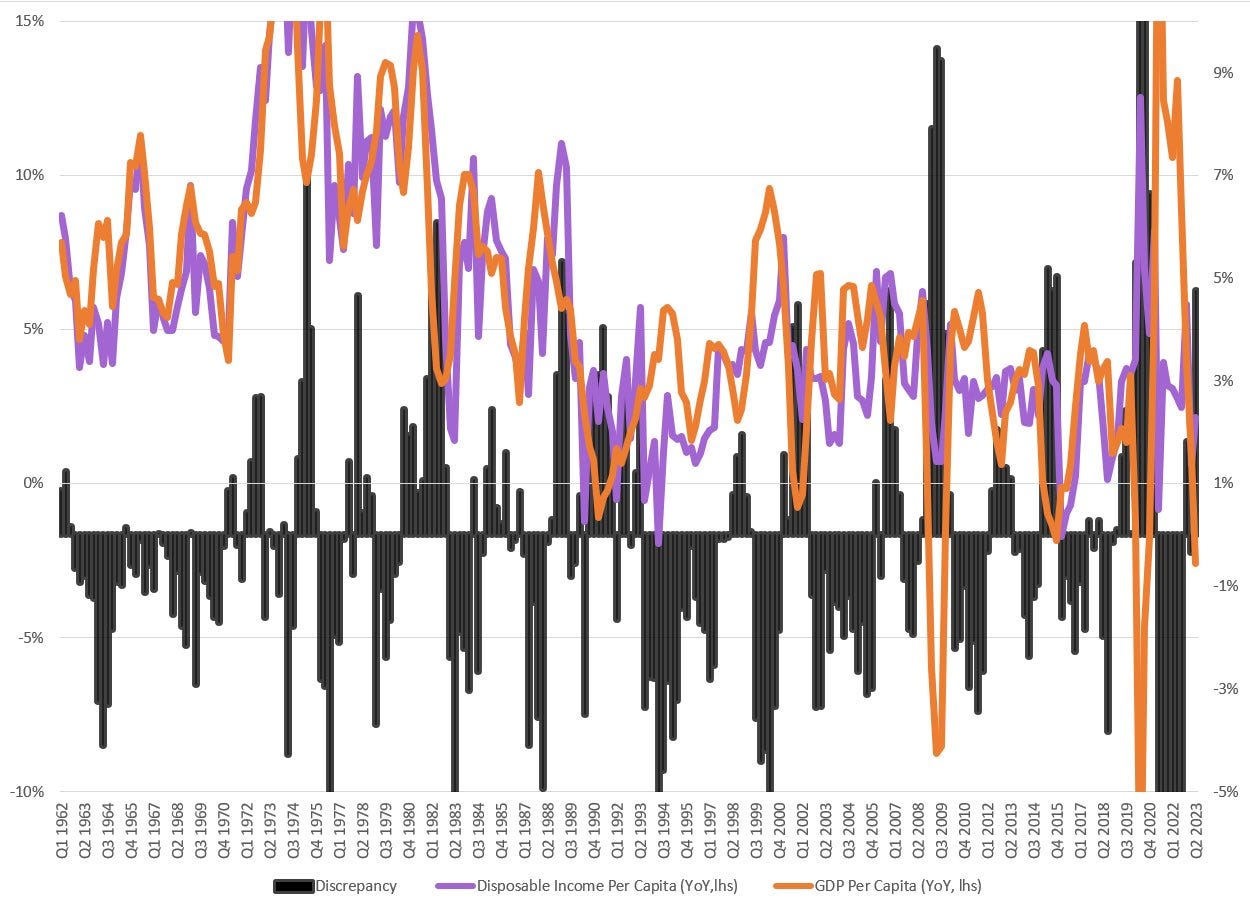

One of the most logical starting points is to examine GDP, as it is a commonly used indicator of a country's economic health and growth potential. GDP allows us to assess factors such as output, consumption, and other economic dimensions. In the realm of Canadian economics, there has been significant discussion regarding GDP per capita and its contraction. Many argue that this contraction signals a decline in the material well-being of Canadians. However, GDP per capita is not the most suitable metric for evaluating material well-being.

It's essential to remember that GDP per capita has limited relevance to material well-being unless we assume that all GDP directly benefits Canadians. In reality, some of the GDP goes towards interest payments or is retained by firms to bolster their balance sheets. Additionally, foreign companies may repatriate capital to their home countries, and factors like remittances come into play. A better metric for assessing material well-being is disposable income per capita, which represents the total income received net of taxes.

When measuring disposable income, we consider various components such as compensation, income mix, the operating surplus of the private sector, net property income, current transfers, social benefits, social contributions, and more. One significant factor contributing to differences in disposable income is the share of the operating surplus of corporations in value added and how it correlates inversely with the private sector's well-being. Furthermore, assuming GDP per capita presumes that all production remains within the domestic economy, which is not the case. Factors like balance sheet build-up, government interest payments, remittances, and profits allocated to other countries affect GDP but do not necessarily benefit the domestic private sector.

When we examine household disposable income, we isolate aspects like fiscal outlays, benefits, and other attributes that directly impact the material well-being of the private sector.

In economics, there is the concept of the circular flow, which essentially means that what we spend is what we earn. As a consequence of this, Gross Domestic Income (GDI) is expected to be equal to Gross Domestic Product (GDP). However, we have observed a divergence between these two figures, and while some of this discrepancy may be due to methodological issues, it is interesting to consider tax receipts.

Tax calculations are highly sensitive to household income and corporate profits. What we are currently witnessing in tax revenues suggests that GDI numbers may provide more meaningful insights into the state of the economy than GDP figures. They are pointing to weaknesses in the economy's responsiveness to income changes. In my opinion, this approach offers a better measure of the economic slowdown we are experiencing than attempting to analyze the economy solely by looking at GDP per capita.

Nevertheless, there are multiple ways to assess positive or negative aspects using GDP, and some of these indicators may contradict each other. While some are contracting, others are showing positive trends. Additionally, we have other metrics like Gross Domestic Income (GDI) pointing to a deterioration in the sector of the economy that is most sensitive to changes in incomes. However, if we focus solely on GDP, it has proven to be more resilient than many had expected.

Many were anticipating significant negative GDP prints year-over-year. However, the fiscal authorities have implemented a substantial increase in the fiscal impulse, which tends to have a profound impact on overall GDP. This impact is often channeled through increased consumption. One way to measure this is by examining outlays, which represent direct cash injections. Most of the time, increases in fiscal outlays (growing by 10% YoY in Canada) have a substantial effect on shifting the aggregate demand curve to the right, or at the very least, offsetting higher interest rates that would otherwise affect aggregate demand through the interest rate channel. This fiscal stimulus has played a crucial role in keeping Canada's GDP growing at a positive rate year-over-year.

However, this approach poses a problem for Canada. Unlike the United States or the Eurozone, Canada is not a reserve currency, which means that it cannot sustainably monetize over its productive capacity. While Canada can maintain this for a short period, doing so will lead to higher nominal GDP growth rates than nations that aren't pursuing this strategy. For instance, over the last decade, Canada's nominal GDP growth has outpaced that of the United States. However, this is not a sustainable path.

The second issue is that such a strategy will result in the devaluation of the Canadian currency, leading to higher inflation rates. Canada has been pursuing this approach for an extended period, and recently, monetization over productive capacity has seen a parabolic increase. While this may contribute to continued upside in Canadian GDP, it comes at the cost of higher inflation rates and currency devaluation.

This leads to the next issue, which is the impact on the Canadian dollar. The Canadian dollar has been considerably weak, and I anticipate that this trend will continue. Canada appears to have reached a point where monetization over productive capacity is negatively affecting the Canadian dollar. This is evident in the term structure of the foreign exchange (FX) market, where you observe a widening effect further out on the maturity curve, typically around the 1-year mark. This reflects the market's implicit pricing of macroeconomic risks for Canada. One of these risks is what was highlighted earlier: monetization over productive capacity. Historically, when Canada engages in such practices, it often results in a devaluation of the Canadian dollar.

Continuing on the previous point, when a country experiences a weakening currency, it affects its terms of trade, and this, in turn, can lead to Canada importing inflation. This inflation transmission happens through both the import channel and the export channel. As Canadian goods become more affordable for foreigners, there is increased foreign demand, which theoretically, given the current supply-side constraints, leads to higher price levels.

Canada currently doesn't produce enough domestic surplus to satisfy consumer needs, resulting in a trade deficit. With others competing for Canadian goods, this pushes up domestic prices and increases the price of imported goods for consumers. This, in turn, contributes to an overall increase in the inflation rate for Canadians, primarily through import-driven inflation. We can observe how monetization over productive capacity tends to coincide with higher rates of inflation in Canada.

Now that we've discussed these issues, it's important to acknowledge that they could potentially harm the well-being of Canadians. Higher prices have a detrimental effect on consumers and, in fact, on nearly everyone throughout the economy. The problem is compounded by Canada's relatively weak productivity, which further reduces the standard of living for Canadians.

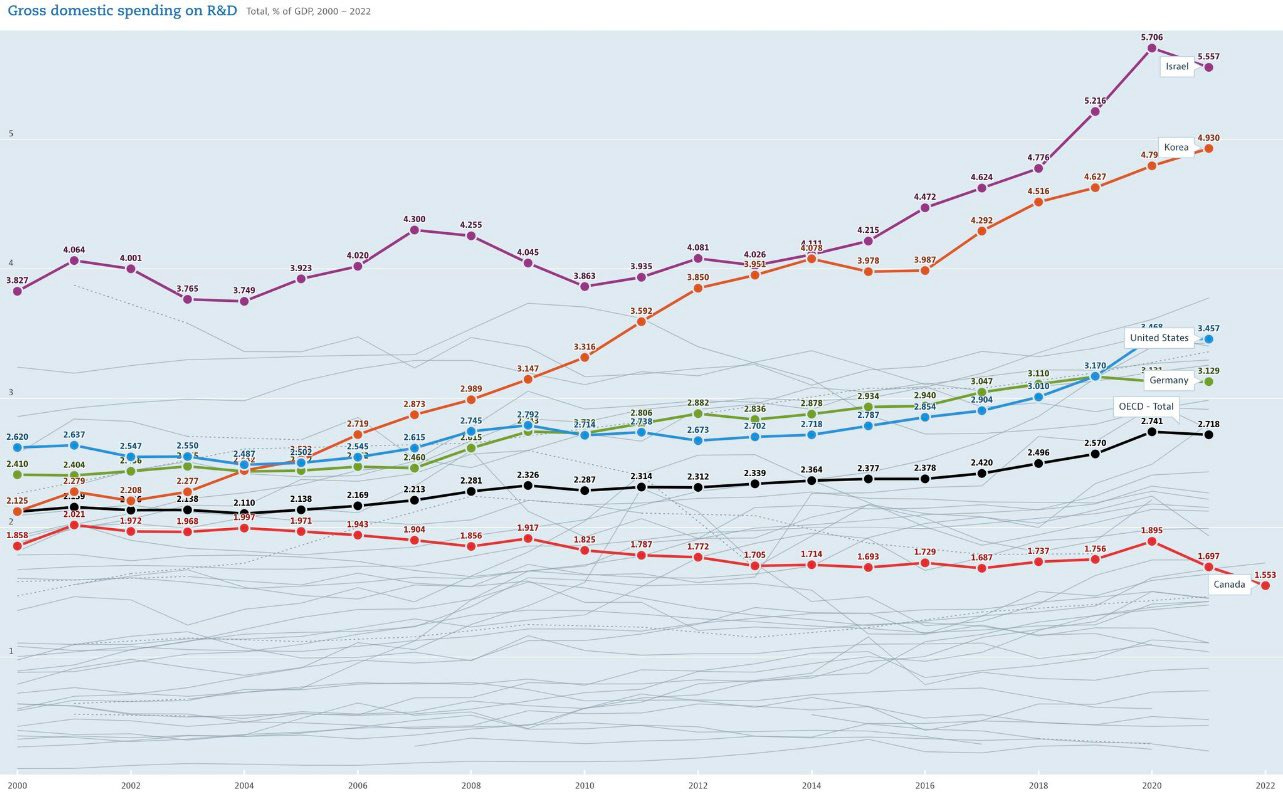

I'm a strong believer in the Solow Growth Model, which essentially asserts that factors leading to long-term improvements in the standard of living include capital per worker, investment in the capital stock, total factor productivity, and output. These elements work in concert: when there's more capital per worker, and that capital is efficient, it results in increased output. This is achieved through the growth of the capital stock, including plants, machinery, and equipment, as well as investments in research and development (R&D).

The issue with Canada is its relatively low levels of R&D as a percentage of GDP. This means that workers are using equipment that is less productive than it could be otherwise.

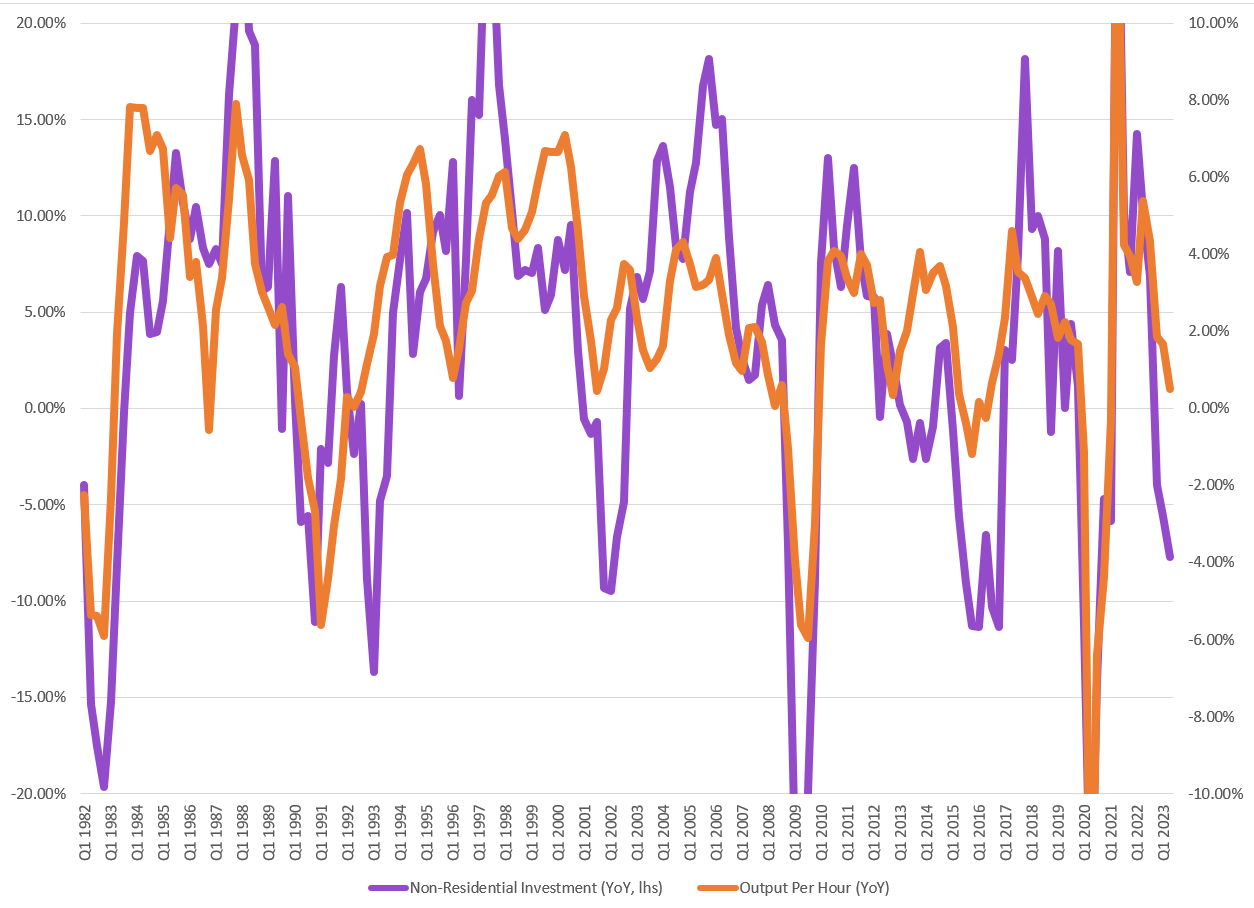

Let's delve into the concept of capital deepening and why it's vital for improving the standard of living. Capital deepening measures the amount of capital available and how efficiently that capital is utilized, directly influencing output.

This ratio indicates whether the current additions of capital are depreciating more rapidly than the labor force. This relationship has a significant impact on output, which, in turn, plays a crucial role in raising the standard of living.

So, where does Canada stand in terms of capital deepening? When we examine how much is invested in Canadian workers or capital intensity, we find that Canadian businesses spend approximately $15,000 per worker. In contrast, the United States invests nearly $25,000 per worker.

This situation leaves the consumer in a vulnerable position, given the lower level of investment directed toward the worker. However, things could worsen further due to the overall weakness in the labor market. It's important to remember that business capital expenditure (capex) has a multiplier effect on economic activity. You might be wondering what this means. Hiring activity has a positive multiplier effect on wage incomes, which, in turn, aids in completing the circular flow model we discussed at the beginning of this article.

What we are currently observing is a continued weakening of fixed investment in Canada. This implies that business spending on factors of production is on the decline. Additionally, it's notable how fixed investment, as discussed, closely tracks the marginal propensity to consume. While the correlation isn't perfect, you can somewhat see the multiplier effect in action as we discussed.

We can also observe how fixed investment has a direct impact on output, as it signifies either an increase or decrease in the allocation of capital to workers, potentially leading to a positive impact on factors of production and, consequently, an overall increase in output.

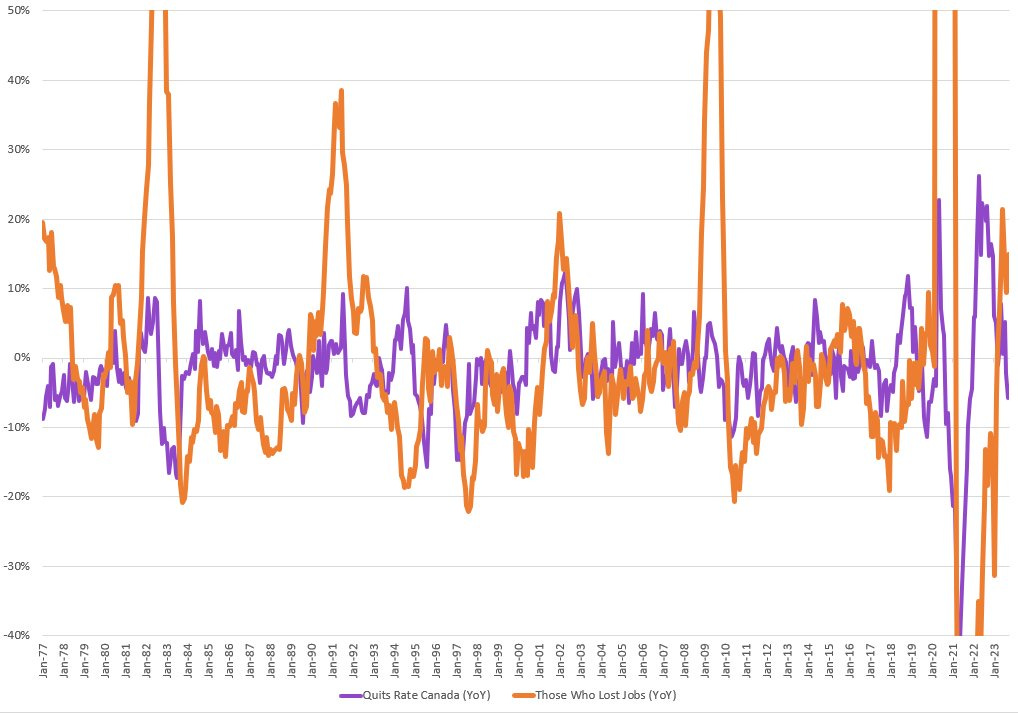

Currently, it appears that output is declining in tandem with the significant slowdown in fixed investment. If production slows down, and labor is no longer as productive or needed to meet the existing level of demand, it can result in job losses.

This brings us to the job market, which is now showing signs of weakening. Job losses have reached levels typically seen during recessionary periods. There has been an increase in job separations, including those who have lost their jobs for various reasons, and this trend usually corresponds with higher quit rates. However, we are observing a divergence between these two indicators.

The fiscal impulse has been instrumental in helping many weather the storm, contributing to increased savings and influencing the marginal propensity to repay debt.

We are also witnessing an increase in the government deficit as a percentage of GDP. This typically occurs during periods of rising unemployment because the government aims to stimulate the economy through fiscal measures. What is noteworthy is that it appears the government is already taking action to anticipate the slight uptick in the recent unemployment rate.

However, there are some flashing signs of a recession, and one very interesting aspect is the behavior of construction payrolls leading up to economic downturns. There are a few reasons for this. First, changes in present-discount-value alter the attractiveness of projects for commercial purposes and increase the cost of ownership for residential properties. This, in turn, causes investors to hold off on new construction, leading to a slowdown in the demand for builders.

A second aspect to consider is the relationship between housing starts and completions, which can help identify the backlog in relation to the rate of housing completion. As you begin to work through and complete projects that were once started, and as the demand for new starts decreases, construction payrolls start to decline.

As mentioned at the beginning of this article and reiterated above, we can observe the fiscal authority taking the lead in steering the direction of the Canadian economy. This shift is a response to the current levels of debt that Canada is exposed to. It's widely known that a significant portion of household sector debt in Canada is variable. Consequently, interest rates play a more substantial role in constraining consumption compared to the United States.

In Canada, changes in interest payments can result in a significant alteration of household leverage over time (albeit with a lag). As interest payments surge, this is expected to substantially increase household leverage as a percentage of GDP in the following quarters. Such a scenario would mean that interest rate impacts, in the absence of fiscal stimulus (which is substantial), could significantly dampen aggregate demand within the Canadian economy. Interest rates act as a constraint on the marginal propensity of consumption.

This dynamic differs significantly from the United States, where we can observe that, despite a substantial increase in interest rates, the flow-through effect has been relatively flat. This is mainly due to the significant differences in mortgage structures between the two nations. The ability for United States households to lock in historically low rates for 30-year mortgages has enabled them to be highly insulated from the effects of higher interest rates. This has been a major contributing factor to the continued strength in consumption trends in the United States.

An interesting observation is that aggregate loan-to-values have decreased in Canada, which is a positive sign. However, household leverage has substantially increased to drive the debt-to-assets ratio.

The fact that leverage is starting to decline could potentially take some of the momentum out of the housing market. The Bank of Canada (BoC) itself has noted that fixed-rate mortgage payments at renewal will be at their highest in 2025 and 2026, rising from 20% to 25%.

For homeowners with variable-rate fixed-payment mortgages, they will need to increase their payments by about 40% to maintain their original schedule.

Approximately 67% of mortgages in Canada have fixed rates with short durations. The remaining 33% of mortgages have been significantly affected by changes in interest rates.

Variable rate mortgages experienced rapid growth at the outset of the pandemic. Within the variable mortgage category, about 75% of them have fixed payments, which means that as interest rates increased, the monthly payments remained the same, but a smaller proportion of the payments went toward the principal.

Recently, there has been an increase in new extensions within the fixed-rate category, particularly for durations of 3-5 years. However, as highlighted by the Bank of Canada (BoC), these mortgages will start to feel the financial strain beginning in 2025-2026.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) has emphasized the vulnerability of variable rate mortgages with fixed payments when interest rates increase.

At some point, as these rate hikes continue, mortgages reach a stage where the monthly payment covers only the interest payment and no capital repayment.

According to the BoC, as of their October summit last year, around half of the variable rate mortgages with fixed payments (approximately 15% of all mortgages) had reached a trigger rate.

With the current economic outlook, this number is expected to continue rising over the next couple of quarters.

As interest rates rise, we will continue to observe negative amortization. While allowances for negative amortization exist, these borrowers will require a new loan at the end of the original term, with much higher payments than before.

This is a point where we could potentially witness ongoing financial instability within Canada.

However, despite the high levels of debt, consumption levels have remained resilient, which, as highlighted at the beginning, can be perplexing for many. The substantial increase in net housing wealth, along with other sources of wealth such as equity markets, has led to one of the most significant year-over-year increases in wealth over the last 30+ years.

In assessing this, I consider all financial wealth and deduct it from liabilities, relative to disposable income. While this ratio has experienced a decrease in percentage change, we are now witnessing a rapid V-shaped recovery. This implies that consumption will persist through the wealth effect channel in Canada.

As a result, more households will consume out of their current income, leading to a reduction in the savings rate for Canadians.

Now there have been concerns about government debt given the significant levels of debt in the economy, but the Canadian government is well insulated. When we examine the overall debt service ratio, it remains significantly lower compared to where it was 10 years ago. As the term of debt has increased, overall debt service payments have remained either flat or have declined, and they have not increased at a similar rate to the rise in interest rates. Even when considering the recent trend and the substantial increase in interest rates, Canada's government debt service ratio remains at levels similar to what it has been for the past 14 years.

As pointed out in this article, there are certain aspects of the economy that give rise to concerns, but I believe that the prevailing pessimism might be somewhat exaggerated. It's essential to examine the areas of the economy that continue to display remarkable resilience.

The main takeaway from this analysis is that the fiscal authority is playing a crucial role in shoring up the weaknesses that might otherwise be more pronounced. As long as the fiscal impulse remains robust and continues to grow, I am optimistic that this will prevent a significant slowdown in the economy. Furthermore, it will provide a boost to the household budget constraint, allowing for an increase or, at the very least, an offset to the impact of the higher interest rates that we are currently witnessing.